You Were Born to Fear Snakes - Here’s Why

May 05, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

The longest snake alive today is the reticulated python—a creature that can stretch over 20 feet long and squeeze the life out of animals much larger than itself. It lives in the rainforests and wooded areas of Southeast Asia. It kills not with venom, but with crushing force—wrapping its coils tighter with every exhale its prey takes.

But even that giant is dwarfed by more ancient monsters. In 2023, scientists described a new extinct species called Vasuki indicus—a snake so massive it could have reached 50 feet long, rivaling the girth of a car. It lived in India over 47 million years ago, slithering through the jungle like a prehistoric nightmare.

And snakes like these weren’t rare freaks of nature—they were part of a whole evolutionary gauntlet our ancestors had to survive through. For millions of years, early mammals, primates and hominins shared their world with giant constrictors, venomous vipers, fast-striking cobras, and other camouflaged predators lurking in trees, grass, and water. These predators were ready to ambush at any moment, so our ancestors had to be ready to fight or flee.

The fear of snakes isn’t just superstition or bad luck. It’s something deeper. Something hardwired.

In this video, we’ll explore how snakes shaped human evolution—not just physically, but psychologically and culturally; Why we’re programmed to be fearful of them from birth; And why they appear in myths, dreams, and symbols around the world. And after you hear what the science says, you’ll understand how our two lineages have been in a true evolutionary arms race for millions of years.

From deep within our brains to the stories we tell, the serpent’s influence runs rampant. We may have left the jungle, but the snake never left us.

Watch the full YouTube Video HERE.

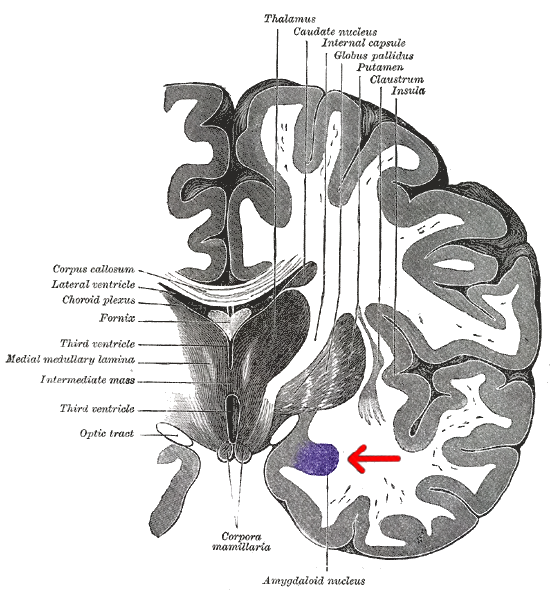

The Evolutionary Psychology of Fear

Fear isn’t just an emotion—it’s a survival mechanism hardwired into our brains. At the heart of the fear response is the amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure that acts as an internal alarm system. When a potential threat is detected, signals rush to the amygdala, triggering the classic fight-or-flight response in a matter of milliseconds. Our visual cortex also evolved to detect specific threat shapes, like the sinuous curve of a snake, incredibly fast—often before we even consciously recognize what we’re seeing.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this made perfect sense. Quick, instinctive reactions to dangers like heights, spiders, or aggressive animals helped our ancestors survive and pass on their genes. Fear helped ancient humans stay cautious, alert, and alive. And some fears, like the fear of snakes, seem especially deeply rooted. Research shows that even infants as young as 8 months are quicker to spot images of snakes compared to harmless animals or flowers. In experiments with young children and adults, people consistently detected striking snakes faster than resting ones, even in black-and-white images.

Brain scans add another layer of evidence. Studies measuring Early Posterior Negativity (EPN) show that visual areas of the brain light up more strongly in response to snakes than to spiders, slugs, or other animals. What’s remarkable is that these physiological responses often kick in before people are even consciously aware they’re looking at a snake. By the early 2000s, all this research was pointing to the same conclusion: humans are born to fear snakes. In 2006, anthropologist Lynn Isbell formally proposed the Snake Detection Hypothesis, suggesting that snakes didn’t just terrify our ancestors—they helped shape the evolution of primate vision and vigilance itself. In a very real way, snakes helped make us who we are.

Snakes as Prehistoric Predators

Primates

Our story as humans doesn’t begin with stone tools or fire—it goes back much further, to the earliest primates who lived 55 to 66 million years ago. These small, tree-dwelling mammals, like Purgatorius and other early plesiadapiforms, thrived in the dense forests of ancient North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. Adaptations like grasping hands, forward-facing eyes, and nails instead of claws helped them navigate the treetops and distinguish them from other mammals. As their reliance on vision grew, it set the foundation for one of the most defining features of primates, including us.

Scientists have long debated why primates evolved these traits. The Arboreal Hypothesis argues that sharp vision and dexterous hands evolved to move through trees. The Visual Predation Hypothesis suggests these traits helped primates hunt insects in dense foliage. The Angiosperm Coevolution Hypothesis proposes that early primates evolved color vision to spot ripe fruits. Yet, Lynn Isbell introduced another powerful idea: the Snake Detection Hypothesis. She proposed that snakes—ancient, stealthy predators—were a major driver behind primate evolution, pushing for better vision, faster reflexes, and stronger fear responses.

Research now supports this view. Studies show that primates who lived longest alongside venomous snakes—like Old World monkeys, apes, and humans—have the most advanced vision systems and show instinctive fear toward snakes. Meanwhile, Malagasy primates, who evolved without venomous snakes, have poorer eyesight and less fear. Some primates even evolved a degree of toxin resistance to snake venoms, particularly to the α-neurotoxins found in cobras. It appears that millions of years of evading snakes didn’t just make primates better survivors—it fundamentally rewired their brains and bodies, laying critical groundwork for what would eventually become human intelligence.

Humans

Although direct fossil evidence is scarce—since snakes often digest their prey whole—there’s little doubt that early humans, like other primates, had frequent and dangerous encounters with snakes. Today, snakebites still cause around 94,000 deaths globally each year, particularly in rural regions where people live closer to traditional, hunter-gatherer lifestyles. For example, in Mozambique, nearly 70,000 snakebites occur annually, with a strikingly high fatality rate.

Modern hunter-gatherer groups offer even deeper insights. Among the Agta people of the Philippines, 25.9% of men have been attacked by pythons, usually while hunting in dense forests—mirroring the risks ancient humans would have faced. Similarly, in Ecuador, studies of the Waorani reveal that 45% of the population has experienced at least one snakebite, with snakebites accounting for 4% of all deaths. These real-world examples highlight just how dangerous the human-snake relationship has historically been.

Even without fossils, the evolutionary patterns are clear: snakes were not passive background threats, but active, deadly predators that helped shape our behavior, senses, and even our brains. And while modern life has removed many of us from these daily dangers, the fear persists—living on through the powerful stories, symbols, and myths that humans created to make sense of a world filled with hidden threats.

The Serpent Symbol: A Cultural Universal

In recent years, our understanding of genetics has expanded to include epigenetics—the idea that behaviors and environmental factors can change how genes function without altering the DNA sequence itself. Similarly, intergenerational trauma shows that emotional experiences can echo across generations. Mechanisms like these suggest that the deep-seated symbolism of snakes in human culture may not be purely conscious invention, but rather a lasting imprint of evolutionary encounters with real, deadly threats.

Across civilizations, the snake appears in strikingly similar roles. In Judeo-Christian tradition, the serpent in Eden represents temptation and deception, planting the seeds of moral failure. In contrast, the Ouroboros of ancient Egypt and Greece—a snake eating its own tail—symbolizes eternity, rebirth, and the endless cycle of life. In Hindu and Buddhist traditions, Nāgas embody the dual forces of nature: guardians and protectors, but also vengeful when disrespected. Meanwhile, in Mesoamerica, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, symbolizes wisdom, creation, and the merging of earth and sky—casting the snake not as a villain, but as a civilizing force.

The snake’s dual role extends into the practical world too. The Rod of Asclepius, still used as a symbol of medicine today, links the snake’s regenerative qualities to healing and resilience. Venom, once a deadly threat, became a source for lifesaving treatments—a powerful reminder that danger and cure are often two sides of the same coin. Even dragons, magnified versions of snakes in global mythology, reflect this ancestral fear; slaying a dragon becomes the ultimate act of conquering chaos and mastering survival. Whether as enemy, protector, teacher, or symbol of transformation, the snake forces us to confront both our vulnerabilities and our ability to overcome them. But humans weren’t just shaped by snakes—we also shaped them. And that's where the story turns next.

Humans as Prehistoric Threats

Snake bites are often defensive rather than predatory—just as we fear snakes, they fear us. It's easy to think of humans as passive recipients of evolution, but when it comes to snakes, the relationship is two-way. We didn’t just adapt to survive snake encounters; snakes adapted to survive encounters with us.

Most snake venoms evolved to hunt prey, but in spitting cobras, venom took on a new purpose: defense. These snakes evolved the ability to spray venom directly into the eyes of threats, causing immediate, searing pain. Even more remarkable, this adaptation evolved independently in three separate cobra lineages—African cobras, Asian cobras, and the rinkhals. Their venom evolved to target mammalian sensory neurons, prioritizing pain over paralysis.

Who were they defending against? A 2021 study points to early humans and their ancestors. Spitting in African cobras appeared around 7 million years ago, just as early hominins emerged. Asian cobras evolved this trait around 2.5 million years ago, aligning with the spread of Homo erectus into Asia. Humans are unique in actively hunting and killing snakes, often using tools—making us a powerful evolutionary force. Just as snakes drove humans to evolve sharper senses, humans drove snakes to evolve new chemical weapons. It’s a vivid example of coevolution—an ancient arms race that still echoes today.

Sources:

[1] Datta, D., and Bajpai, S. 2024. “Largest known madtsoiid snake from warm Eocene period of India suggests intercontinental Gondwana dispersal.” Sci Rep 14, 8054.

[2] LoBue, V., and DeLoache, J. 2010. “Superior detection of threat-relevant stimuli in infancy.” Dev Sci. 13(1):221-8.

[3] Masataka, N., et al. 2010. “Human young children as well as adults demonstrate 'superior' rapid snake detection when typical striking posture is displayed by the snake.” PLoS One. 5(11):e15122.

[4] Van Strien, J., et al. 2014. “Testing the snake-detection hypothesis: larger early posterior negativity in humans to pictures of snakes than to pictures of other reptiles, spiders and slugs.” Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:691.

[5] Ohman, A., and Soares, J. 1993. “On the automatic nature of phobic fear: conditioned electrodermal responses to masked fear-relevant stimuli.” J Abnorm Psychol. 102(1):121-32.

[6] Soares, J., and Ohman, A. 1993. “Preattentive processing, preparedness and phobias: effects of instruction on conditioned electrodermal responses to masked and non-masked fear-relevant stimuli.” Behav Res Ther. 31(1):87-95.

[7] Isbell, L. 2006. “Snakes as agents of evolutionary change in primate brains.” J Hum Evol. 51(1):1-35.

[8] Van Le, Q., et al. 2013. “Pulvinar neurons reveal neurobiological evidence of past selection for rapid detection of snakes.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Nov 19;110(47):19000-5.

[9] Harris, R.J., et al. 2021. “Monkeying around with venom: an increased resistance to α-neurotoxins supports an evolutionary arms race between Afro-Asian primates and sympatric cobras.” BMC Biol 19, 253.

[10] Farooq, H., et al. 2022. “Snakebite incidence in rural sub-Saharan Africa might be severely underestimated.” Toxicon. 219:106932.

[11] Headland, T., and Greene, H. 2011. “Hunter-gatherers and other primates as prey, predators, and competitors of snakes.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(52):E1470-4.

[12] Larrick, J., et al. “Snake bite among the Waorani Indians of Eastern Ecuador.” Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 72(5):542-3.

[13] Kazandjian, T. et al. 2021. “Convergent evolution of pain-inducing defensive venom components in spitting cobras.” Science 371,386-390..