In much of the world, maps and documents lead us to ancient sites. But in pre-Columbian America, there’s no written record—archaeology does all the talking. So how do we find violence in the past? The landscape gives us clues. Terraces, walls, and strategic views hint at defensive planning. Crop marks reveal buried structures. LiDAR and ground-penetrating radar expose ditches, palisades, and moats.

Excavations confirm the evidence—postholes, burned walls, weapons, and trauma. Piece by piece, a fortified community emerges. And across North America—Canada, the U.S., and Mexico—the story shifts with each landscape and culture.

Canada

Schaepe, D. 2006. “Rock Fortifications: Archaeological Insights Into Precotact Warfare and Sociopolitical Organization Among the Stó:lō of the Lower Fraser River Canyon, B.C.” American Antiquity 71(4):671.

Alaska and Canada were the first lands seen by early Native Americans. Around 20,000 years ago, people skirted the Pacific coast, avoiding massive ice sheets, and later migrations pushed inland. In the Lower Fraser River Canyon of British Columbia, humans have lived for 10,000 years. Early camps like Milliken and Glenrose reveal hunter-gatherers, rich salmon harvests, and the foundations of Northwest Coast culture.

The Stó:lō people later built villages along the river, their lives shaped by salmon. But their oral history also preserves stories of warfare—lookouts, ambush sites, burned villages, and raids for dried fish. These traditions align with archaeologist David Schaepe’s findings.

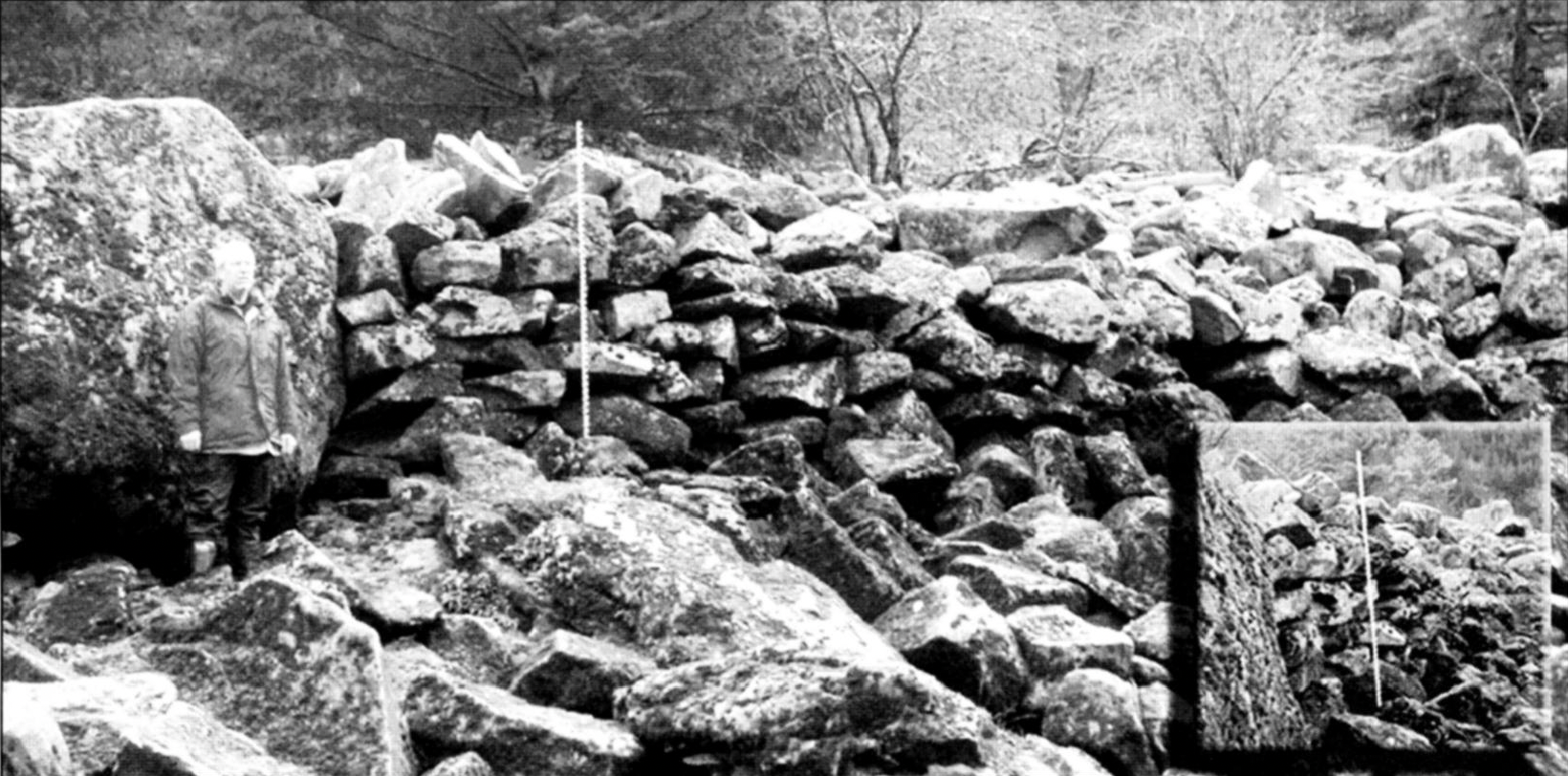

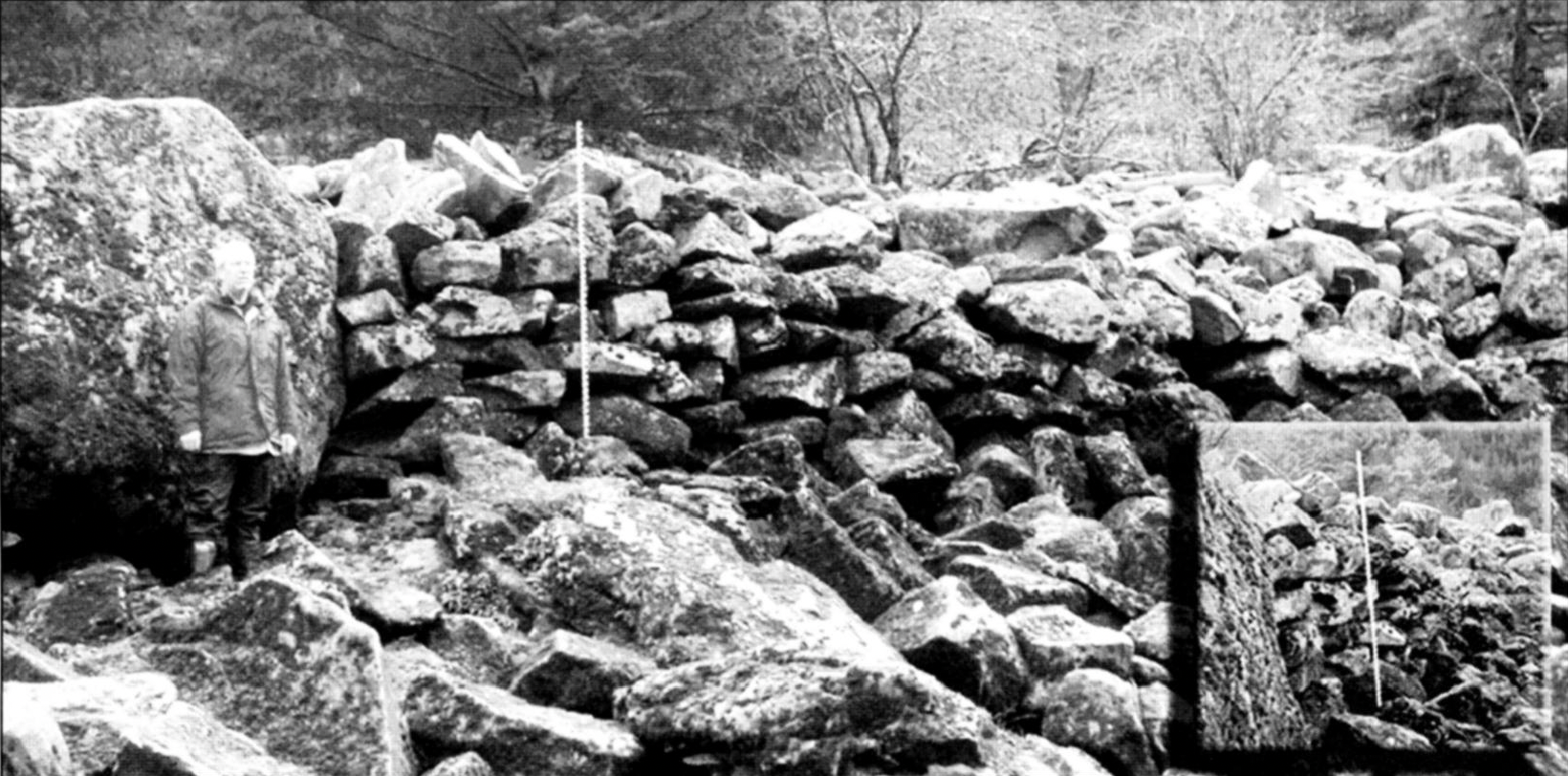

Schaepe identified a network of stone fortifications dating from 1500–1800 AD. The steep canyon walls and abundant granite allowed communities to build four types of defenses: freestanding boulder walls, retaining walls, raised platforms, and lines of placed boulders. These structures fronted villages, guarded canoe landings, and controlled chokepoints. Some stretched for over 100 meters and required moving massive stones by hand.

Multiple lines of evidence support their military purpose. Archaeology shows strategic placement and associated weapons like projectile points and sling stones. Early European accounts describe palisades, ladders, and intertribal raids. Stó:lō oral histories recount battles, lookout points, and villages burned by coastal attackers—often motivated by the region’s most precious resource: salmon.

Together, the physical remains, historical records, and Indigenous memories reveal a fortified landscape shaped by competition, survival, and the defense of vital riverine territory.

The United States

As we move from the cliffs of British Columbia into the heart of the United States, fortifications take on new shapes. Here, mound-building cultures flourished for thousands of years. Early Archaic sites like Watson Brake and Poverty Point (3500–1000 BC) show some of the first monumental constructions in North America—massive earthen works built by mobile hunter-gatherers for ceremonial purposes. But everything changed in the Woodland and Mississippian periods.

During the Woodland period, pottery, farming, and long-distance trade spread. Populations grew. By 800 AD, this world transformed into the Mississippian culture: a network of complex chiefdoms centered on the Mississippi and Tennessee River Valleys. They built enormous towns, rigid hierarchies, and more than anything—fortifications.

Mississippian sites used large wooden palisades, often with bastions spaced 20–40 meters apart for bow-and-arrow defense. Over 30 fortified sites have been identified, revealing widespread militarization.

Cahokia, the largest pre-Columbian city north of Mexico, fortified its sacred core—Monks Mound and the Grand Plaza—with a huge bastioned palisade rebuilt four times between 1200–1400 AD. Each rebuild shows evolving defensive strategy. This wasn’t about defending common folk. It was about guarding power.

Other mound centers followed suit. Moundville in Alabama sat behind a mile-long palisade using the Black Warrior River as its fourth wall. Archaeologists estimate more than 30,000 logs were used to build it—a massive public labor project meant to deter attack. It worked: unlike many Mississippian towns, Moundville shows no evidence of burning.

Etowah in Georgia went even further. Its bastioned palisade stood just inside a deep, 9–10-foot moat. Yet even these defenses failed. The palisade burned, the site collapsed, and elite burials show signs of chaos—likely marking a violent end.

Across North America, fortifications reveal a continent where warfare shaped cities, landscapes, and political power.

Mexico

Ramón Celis, P. 2024. “Airborne lidar at Guiengola, Oaxaca: Mapping a Late Postclassic Zapotec city.” Ancient Mesoamerica 35(3):899-916.

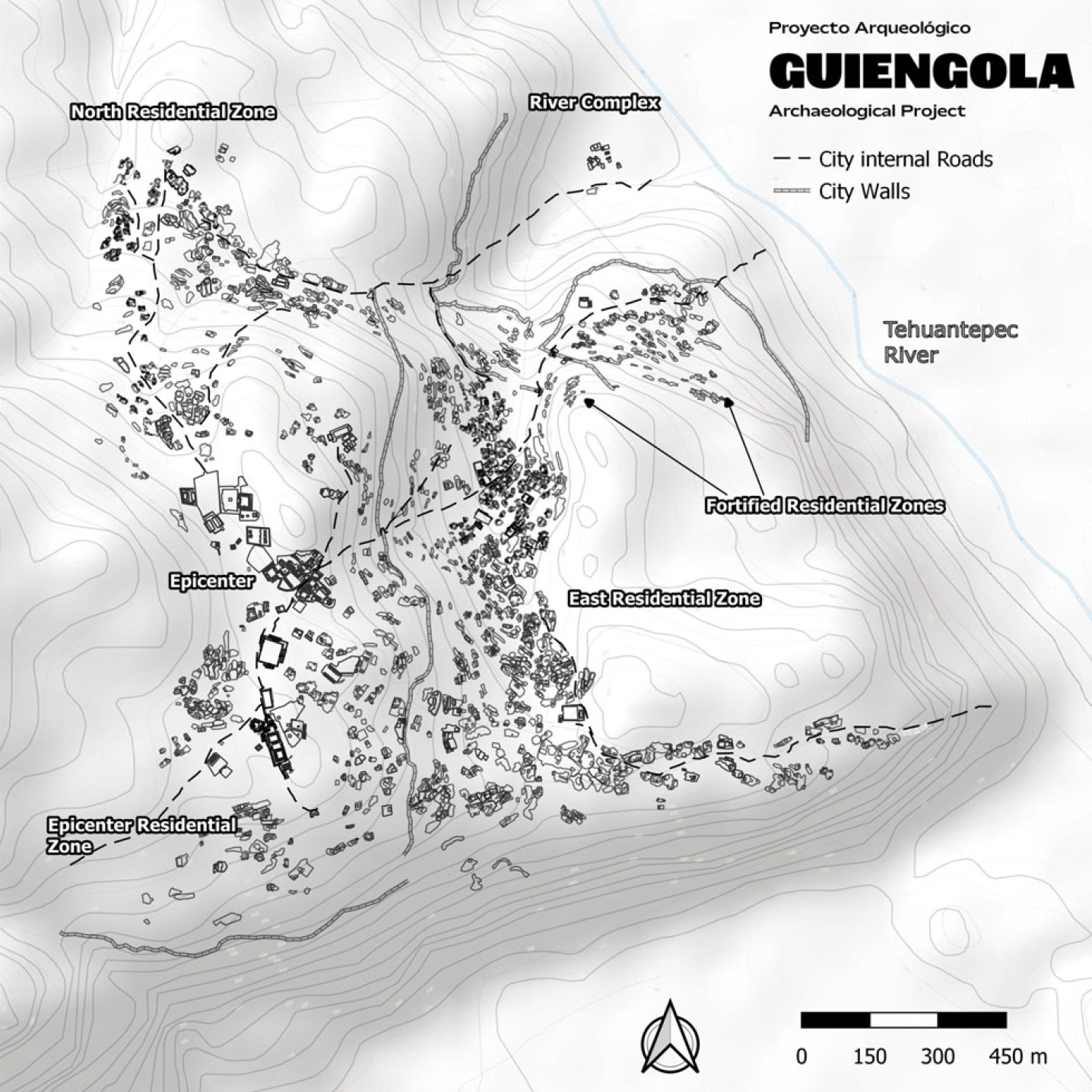

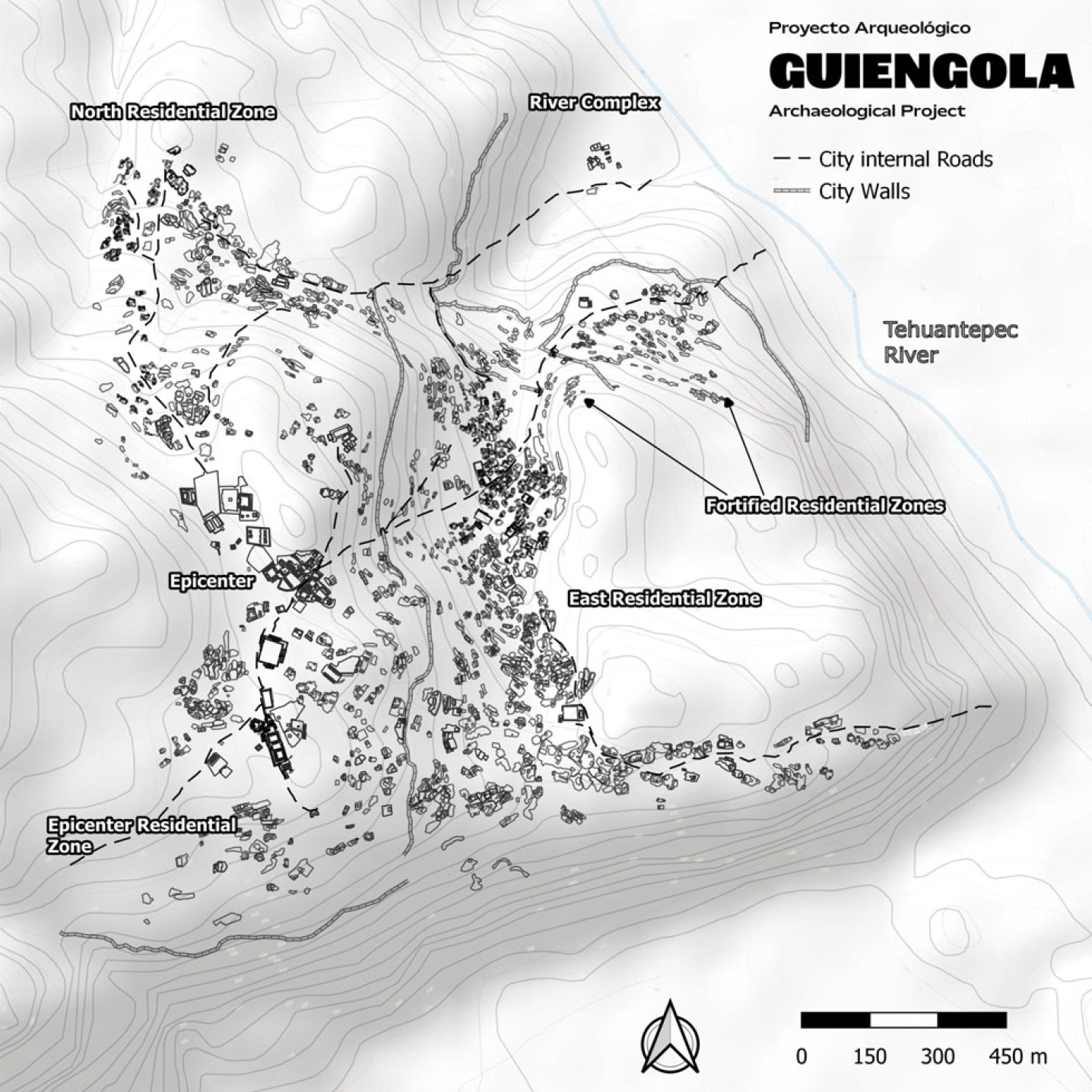

As we move south into ancient Mexico, we find another powerful example of fortified life at the Zapotec stronghold of Guiengola. Perched on a plateau in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the city commands the coastal plain and key river corridors. LiDAR reveals nearly 900 acres of dense neighborhoods, plazas, temples, palaces, roads, and—most importantly—an enormous system of defensive walls.

Guiengola was settled around 1350 AD by Zapotec migrants expanding from the Central Valleys. They entered a region already inhabited by Chontal, Mixe, Zoque, and Huave peoples, but their militaristic expansion aimed to control major trade routes linking the highlands to the tropics. Conflict was expected, and the city’s architecture shows clear preparation for it.

The Guiengola Archaeological Project mapped over 1,000 structures, revealing a full social hierarchy—from elite palaces to commoner barrios. The entire settlement was fortified with tall stone walls, gated checkpoints, and zig-zagging roads designed to slow invaders and create choke points. Square guard structures flanked the gates, indicating controlled entry and constant surveillance.

Most striking are the Fortified Residential Zones (FRZs) on the northeastern edge, where attack was most likely. FRZ 1 had walls up to 5 meters high, protecting ordinary households rather than elites—unlike places such as Cahokia, where defenses centered on ceremonial or political hubs. FRZ 2 connected to the Tehuantepec River and forced attackers through angled roads and narrow kill zones. This was military engineering designed to shield everyday civilians.

Guiengola later became the site of a major showdown between the Zapotecs and the Aztecs. In 1497, Aztec emperor Ahuizotl launched a seven-month siege. The Zapotecs held firm—one of the rare Aztec military failures—thanks in part to the city’s formidable defenses. Guiengola stands as a vivid example not only of ancient fortification, but of Indigenous communities actively defending themselves in a turbulent world.

Sources:

[1] First Peoples of Yale and Spuzzum

[2] THE GLENROSE CANNERY WET SITE: 4,500 YEAR OLD PERISHABLES

[3] Schaepe, D. 2006. “Rock Fortifications: Archaeological Insights Into Precotact Warfare and Sociopolitical Organization Among the Stó:lō of the Lower Fraser River Canyon, B.C.” American Antiquity 71(4):671.

[4] Krus, A. 2016. “THE TIMING OF PRECOLUMBIAN MILITARIZATION IN THE U.S. MIDWEST AND SOUTHEAST.” American Antiquity 81(2):375–388.

[5] Milner, G. R. 1999. “Warfare in Prehistoric and Early Historic Eastern North America.” Journal of Archaeological Research 7(2):105–151.

[6] Keeley, L., et al. 2007. “Baffles and Bastions: The Universal Features of Fortifications.” Journal of Archaeological Research 15(1):55–95.

[7] Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site

[8] Krus, A. 2011. “Refortifying Cahokia: More Efficient Palisade Construction through Redesigned Bastions.” Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, 36(2), 227–244.

[9] Moundville Archaeological Site

[10] Mighty, Mysterious Moundville: 100 years following the first extensive excavations of the famous Mississippian Indian site, questions remain…

[11] King, A. 2003. “Over a Century of Explorations at Etowah.” Journal of Archaeological Research 11(4):279–306.

[12] Ramón Celis, P. 2024. “Airborne lidar at Guiengola, Oaxaca: Mapping a Late Postclassic Zapotec city.” Ancient Mesoamerica 35(3):899-916.

[13] Researchers Thought It Was Just a Fortress. It Turned Out to Be a Lost Zapotec City