When North America Was Underwater

Sep 01, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

What if I told you that Kansas, smack in the center of the United States, once had a shoreline? And beyond that shoreline was an ancient world of creatures long extinct. It sounds like a myth, but it was once a reality. Imagine standing in the middle of those endless wheat fields today - only to realize you’re standing on the floor of a vanished ocean or massive lake.

Now, what if I told you that Native Americans guided colonial explorers in search of what they called “inland seas”? Early mapmakers, working from Indigenous knowledge, sketched coastlines deep in the American interior. Their stories of deep water and lost shores may not have been folklore.

To modern eyes the American interior is just grassland, desert, and Rocky Mountains. But the rocks remember, the geology remembers. They whisper of armored fish, drifting ammonites, and even the footsteps of human ancestors.

Today, we’ll follow the clues these waters left behind, but it’ll take some detective work. Deciphering what the Native Americans were talking about is still not perfectly clear. Uncovering the ghost lakes that once stretched across the landscape is no easy task either. But it’s a story worth digging up. It's a reminder that the world we live in now is not permanent. What we see around us will inevitably change. We can confidently say this because we now know that at various points throughout history, much of North America was underwater.

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Maps, Myths, and Misunderstandings

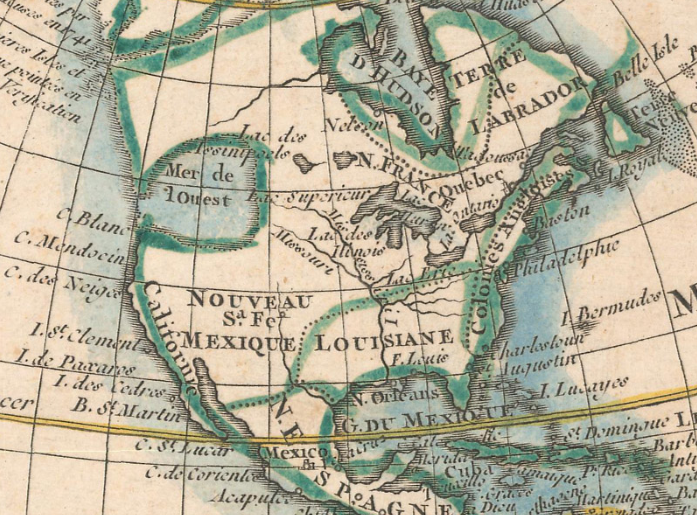

Centuries ago, European mapmakers inked mysterious inland seas across North America—the “Appalachian Salt Lake” in the east and the fabled “Sea of the West” in the northwest. These legends sprang from English explorer John Smith’s captive-told tales of a great sea just a few days’ walk from the coast. Smith’s hand-drawn maps described a river at the 40th parallel flowing into hidden waters—and perhaps even to the Pacific. His reports reached Henry Hudson, who searched in vain for the shortcut to Asia, instead naming the Hudson River.

By the 1700s, the Sea of the West adorned hundreds of maps. Jean Baptiste Nolan’s 1775 chart famously included it—earning him a plagiarism lawsuit—yet it all traced back to secretive 1695 manuscripts by French geographer Gilles de L’Isle, who noted the sea was “known to the natives, though not yet discovered.” Reliant on second-hand Native accounts—Sioux stories of a “great lake with stinking water” or Illinois tales of ancestral shores—European cartographers never set eyes on these waters themselves.

Systematic surveys in the late 1780s finally erased the sea from maps. Most scholars now agree the myths likely pointed not to vast oceans but to real lakes—perhaps the Great Lakes or vanished Ice Age basins—misunderstood through language barriers and Europe’s feverish quest for an Asian passage. Beneath these cartographic ghosts lie hints of ancient shorelines and trade routes—echoes of waters long vanished but never truly forgotten.

Extinct Lakes

Geologists have discovered countless lakes across the Americas, which existed thousands of years ago. They are sometimes referred to as paleolakes or extinct lakes, being that they have since dried up or vastly shrunken. At the time of their existence, people were certainly here. Like all humans, they would’ve relied on water and the resources that flourished along with it. We now know that the human presence in the Americas was well established by 13,000 years ago. I’m sure you’re aware of the Clovis culture, for example, who inhabited North America coast to coast at the time. They were nomadic hunter-gatherers who migrated along rivers and shorelines whenever accessible. People were most likely here well before Clovis, as we’ll discuss later.

Glacial Lake Passaic

New Jersey’s Central Passaic Basin Prehistoric Glacial Lake, Present-Day Wetland Treasure

Long before towns and swampy wetlands filled northeast New Jersey, a 30-mile-long, 200-foot-deep lake—Glacial Lake Passaic—spanned the Newark Basin between 13,000 and 11,000 years ago. That basin began forming over 200 million years ago, when Pangaea split apart and the Watchung Mountains rose from volcanic basalt intrusions, creating a natural bowl.

During the Illinoian glaciation, ice from the Laurentide sheet bulldozed into this bowl, pooling meltwater into the first Lake Passaic. Millennia later, the Wisconsinan ice revived the lake, held back by those same Watchung ridges. When warming finally carved breaches like the Great Notch, the water roared out—dropping the lake by 80 feet and carving today’s Montclair and Clifton valleys.

By 12,000 years ago, Lake Passaic drained into the Passaic River and vanished. Standing atop those ridges now, you see suburbs and skyline—but Clovis hunters once gazed upon a vast, mirror-smooth sea, stalking mastodon and mammoth shores with stone-knapped chert, their footprints lost in the clay and silt beneath our feet.

Lake Agassiz

Minnesota River Basin Data Center

Between the San Andres and Sacramento Mountains once lay a vast 600 sq mi Lake Otero—no glacial pool, but a rain-and-river-filled basin that dried into New Mexico’s White Sands. As the lake evaporated, gypsum crystals rained onto the playa, then wind-ground them into the world’s largest white dune field.

In 2021, archaeologists stunned us with human footprints dated to ~23,000 years ago at Ancient Lake Otero’s edge—long before Clovis—nested beside mammoth and ground-sloth tracks. Critics cried “hard-water effect!” and questioned the sediment context. Now, a new high-resolution study lays the mystery to rest. Twenty-six fresh radiocarbon dates—from aquatic seeds, wetland muds, and pollen—align with the footprints, and isotopes prove no old-carbon trickery. The tracks truly belong to the Last Glacial Maximum.

Even more eerie are parallel grooves etched beside those prints—three distinct types, each slicing or straddling the paths. No animals left them. Scientists believe these are travois drag marks—the world’s oldest evidence of human transport technology, still whispering across the dunes.

Lake Otero

Karen Carr

Between the San Andres and Sacramento Mountains once lay a vast 600 sq mi Lake Otero—no glacial pool, but a rain-and-river-filled basin that dried into New Mexico’s White Sands. As the lake evaporated, gypsum crystals rained onto the playa, then wind-ground them into the world’s largest white dune field.

In 2021, archaeologists stunned us with human footprints dated to ~23,000 years ago at Ancient Lake Otero’s edge—long before Clovis—nested beside mammoth and ground-sloth tracks. Critics cried “hard-water effect!” and questioned the sediment context. Now, a new high-resolution study lays the mystery to rest. Twenty-six fresh radiocarbon dates—from aquatic seeds, wetland muds, and pollen—align with the footprints, and isotopes prove no old-carbon trickery. The tracks truly belong to the Last Glacial Maximum.

Even more eerie are parallel grooves etched beside those prints—three distinct types, each slicing or straddling the paths. No animals left them. Scientists believe these are travois drag marks—the world’s oldest evidence of human transport technology, still whispering across the dunes.

The Western Interior Seaway

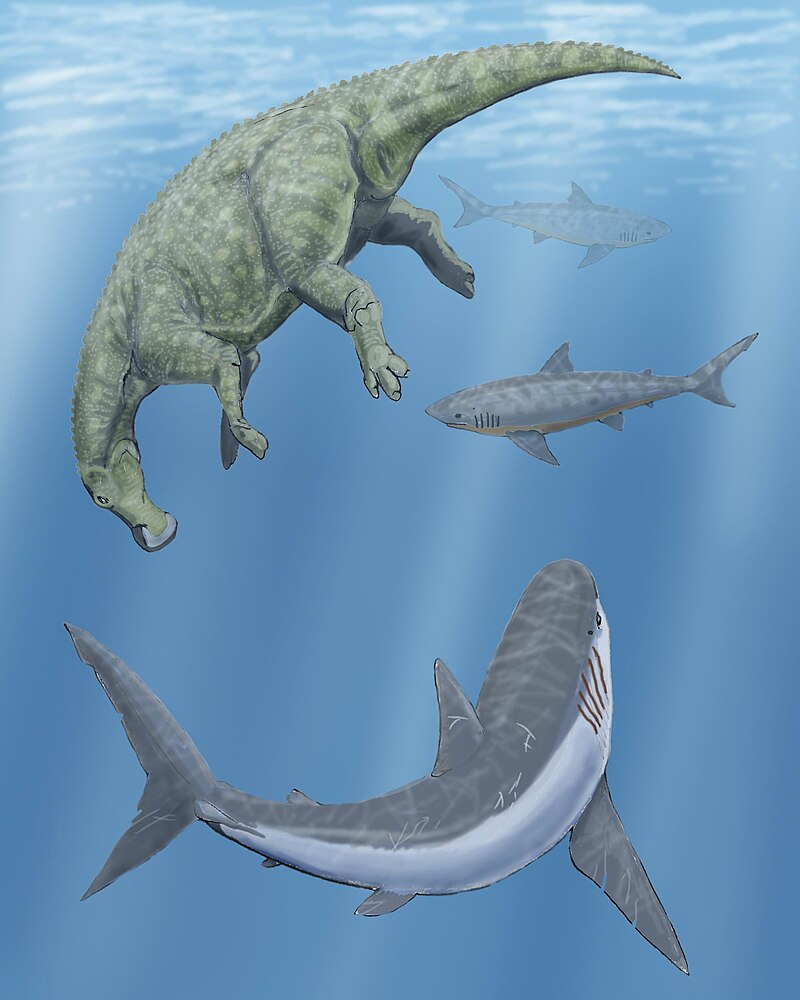

Millions of years ago, a 2,500-foot-deep sea split North America in two—from Texas up through Kansas, Montana, and the Dakotas. This was the Western Interior Seaway. Its warm, shallow waters teemed with plesiosaurs, shell-crushing sharks, and Xiphactinus fish the size of cars. Plankton built chalky plankton-graveyards that now tower as Monument Rocks in western Kansas—70-foot Niobrara cliffs lifted from ancient seabeds.

Local lore says Keyhole Arch began as a single bullet hole in that chalk, slowly widening into a glowing portal—soon to collapse into delicate spires.

Beneath these cliffs lie fossils of diving birds, giant pterosaurs, and meter-wide oyster relatives thriving in oxygen-poor mud. Each tooth and shell whispers of a hidden ocean, its secrets buried in stone. The Western Interior Seaway may be gone, but its ghostly legacy still shapes our plains—and our imagination.

So to bring it all together, North America has by no means been a static continent. Many of the early maps depicting inland seas were most likely based on myths or misunderstandings. However archaeological and geological investigations show us that there were many times when modern lands were underwater. During the time of Indigenous habitations, we find archaeological sites and human footprints in and around giant, extinct lakes. Then, millions of years before them, we find extinct animals that once inhabited ancient seaways.

America is ancient and there's still so much for us to discover.

Sources:

[2] Sanger, M., et al. 2019. “Great Lakes Copper and Shared Mortuary Practices on the Atlantic Coast: Implications for Long-Distance Exchange during the Late Archaic.” American Antiquity 84(4):1-19.

[3] Harper, D. 2013. Roadside Geology of New Jersey. Mountain Press Publishing Company.

[4] Stanford, S. 2007. “Glacial Lake Passaic.” Unearthing New Jersey 3(2).

[5] New Jersey’s Central Passaic Basin Prehistoric Glacial Lake, Present-Day Wetland Treasure

[8] Bennett, M., et al. 2021. “Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum.” Science 373,1528-1531.

[9] Haynes, V. 2022. “Evidence for humans at White Sands National Park during the last Glacial Maximum could actually be for Clovis people ∼13,000 years ago.” PaleoAmerica 8, 95-98.

[10] Pigati, J., et al. 2023. “Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands.” Science 382,73-75.

[11] Holliday, V., et al. 2025. “Paleolake geochronology supports Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) age for human tracks at White Sands, New Mexico.” Sci. Adv.11,eadv4951.

[12] Bennett, M., et al. 2025. “The ichnology of White Sands (New Mexico): Linear traces and human footprints, evidence of transport technology?” Quaternary Science Advances 17, 100274.

[14] Bennett, S. 1994. “The Pterosaurs of the Niobrara Chalk.” The Earth Scientist, 11, 22-25.

[15] Kaufman, E. 2009. “PALEOBIOGEOGRAPHY AND EVOLUTIONARY RESPONSE DYNAMIC IN THE CRETACEOUS WESTERN INTERIOR SEAWAY OF NORTH AMERICA.”

[16] Giant predatory shark fossil unearthed in Kansas

[17] Cumbaa, S. and Tokaryk, T. 1999. “Recent discoveries of Cretaceous marine vertebrates on the eastern margins of the Western Interior Seaway.” in Summary of Investigations 1999. Volume I. Saskatchewan Geological Survey, Sask. Energy Mines, Misc. Rep. 99-4.1.