What Were People Thinking 100,000 Years Ago?

Dec 29, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

Trying to step into the mind of someone from 100,000 years ago isn’t easy. We live in a modern world that reinvents itself every few years. Our realities shift with every new invention, every cultural change. But this pace, the rapid churn of modern life, is an anomaly. For nearly all of human history, life moved slowly. People lived much like their parents and grandparents. Innovation drifted across generations like wind-blown sand. - subtle, gradual, almost invisible.

Entire cultures remained stable for thousands of years. Not because they lacked intelligence or ambition, quite the opposite actually. They were more attuned to their natural world, and acted intelligently within it . We like to think of ourselves as clever, but drop a modern human into the Stone Age and our “brilliance” quickly becomes laughable.

The people who lived 100,000 years ago were not primitive. They had their own ideas about their ancient world, and they were wildly successful at surviving in it. Now, with the tools of archaeology, anthropology, and even cognitive science, we can start to scratch the surface of their inner world. So what were these people thinking about?

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Human Brain Evolution

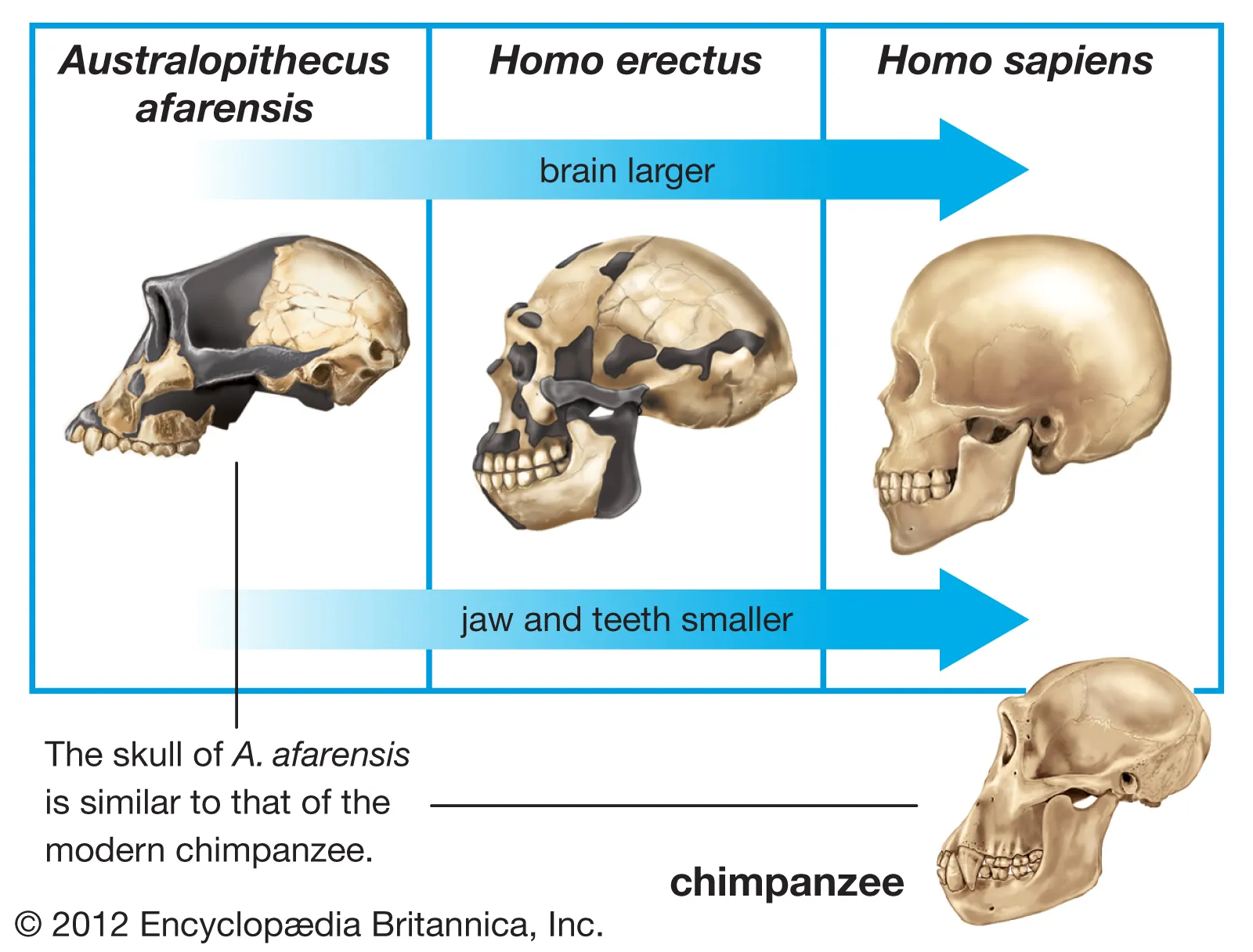

To understand how ancient people thought, we have to start with the organ doing the thinking. The human brain didn’t appear fully formed. It was assembled gradually, layer by layer, across millions of years of evolution.

Around six million years ago, our ancestors were transitioning between forests and grasslands. Their brains were slightly smaller than a modern chimp’s, but walking upright placed new demands on balance, vision, and coordination. The brain wasn’t larger yet—it was reorganizing. Growth continued slowly until about two million years ago, when a major shift occurred. With Homo erectus and later Homo heidelbergensis, brain size nearly doubled. This was the era of fire, long-distance travel, organized hunting, and increasingly complex tools. Natural selection strongly favored individuals whose brains could manage these challenges.

By roughly 300,000 years ago, anatomically modern humans emerged. Brain size reached modern ranges, but the most important change wasn’t just volume—it was expression. Symbolic behavior exploded: pigments, beads, engravings, composite tools, and increasingly complex social lives. The hardware was in place; the software was coming online.

Big brains are costly. They consume enormous energy, so evolution only favors them when the payoff is high. In humans, that payoff came from social cooperation, communication, tool use, and problem-solving. Crucially, the brain didn’t grow evenly. Regions involved in vision, hand control, social perception, and language—especially the neocortex—expanded disproportionately.

Language itself evolved by repurposing older brain systems for sound and meaning, aided by genes like FOXP2. Larger brains also required better internal wiring, leading to faster communication between regions. Finally, long childhoods allowed brains to be shaped by culture as much as genes.

The result wasn’t just a bigger brain, but a reorganized, hyper-connected, culture-driven mind—one that was already fully human by 100,000 years ago.

Ancient Africa

So where were these intelligent people living? Around 100,000 years ago, earth looked much different than today. We were in the middle of the Pleistocene and heading into the last glacial period. It was generally cooler and drier than today, with sea levels dropping and glaciers rising. That said, most of us were still living in Africa. And being closer to the equator, glaciers weren’t too much of a concern.

Africa held sweeping grasslands, dense woodlands, rugged coasts, and inland lakes that rose and fell with changing rains. Homo sapiens were predominantly confined to small groups moving about this continent. Little bursts started to experiment and tread into the middle east and Europe. There they would have encountered other human species like Neanderthals, Denisovans in Asia, and lingering archaic groups in parts of Africa. But here, we're focusing on our specific lineage, living and evolving in Africa.

Ancient Tools and Technology

José-Manuel Benito Alvarez

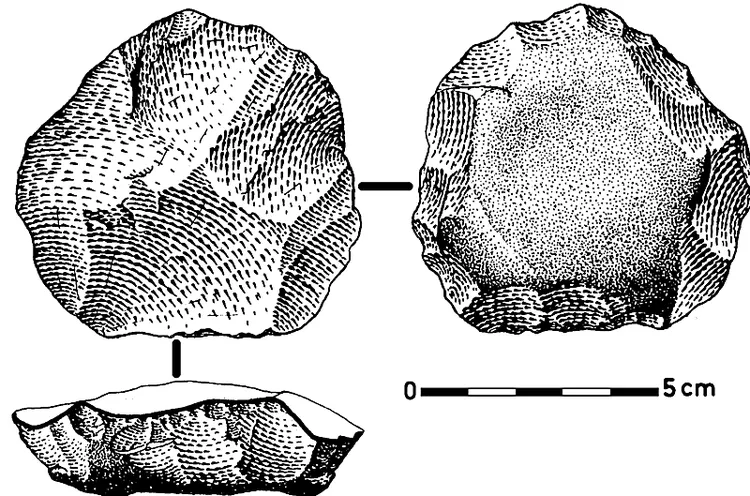

Early Homo sapiens lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers, moving constantly across the landscape. Their camps were temporary, their survival dependent on tracking animals, gathering plants, and—crucially—making tools. Those tools offer a direct window into how their minds worked.

Even the earliest known stone tools, the 3.3-million-year-old Lomekwi choppers, required more foresight than most animal behavior. Made by extinct hominins such as australopithecines or early Homo, these tools were produced using either a passive hammer technique—smashing a stone against an anvil—or a bipolar method using a separate hammerstone. Both required controlled strikes to create sharp edges.

Researchers argue that making these tools demanded three key cognitive skills: planning actions in sequence, precise sensorimotor control, and spatial reasoning—the ability to visualize how removing one flake would affect the next. By the time Homo sapiens appeared, these abilities were deeply ingrained and increasingly refined.

Around 300,000 years ago, stone technology changed dramatically with the Middle Stone Age. Toolmakers began preparing cores so that a single strike produced a predictable flake, as seen in Levallois techniques. By about 110,000 years ago, projectile points diversified rapidly. Many were carefully shaped, pressure-flaked, and hafted onto wooden shafts, requiring the combination of multiple materials and experimental problem-solving.

Recent research suggests these innovations weren’t driven only by strict teaching. Children and adolescents likely played a major role—experimenting, copying imperfectly, and “breaking the rules.” Their mistakes often became innovations, seeding new tool types and traditions. Variation in stone tools, then, reflects not just culture or geography, but generations of curious young minds. In that sense, humanity’s technological success may owe as much to play as to tradition.

What's for Dinner?

Agustin Diaz

Prehistoric humans spent much of their time acquiring and processing food, but they weren’t necessarily starving constantly. Research on modern hunter-gatherers suggests that they often experienced less frequent famine than early agriculturalists. Mobility was key: hunter-gatherers could follow food sources, while farmers were tied to fixed crops, making them more vulnerable during droughts or poor harvests. The same logic likely applied to humans 100,000 years ago.

Archaeology shows that early Homo sapiens had diverse diets. On the South African coast, sites like Pinnacle Point Cave reveal repeated collection of shellfish—mussels, limpets, periwinkles—timed with low tides, showing planning and regular use of coastal resources. At Blombos Cave, antelope bones dominate, suggesting strategic hunting of smaller game and careful exploitation of larger animals for marrow, all while accounting for competition with carnivores.

Plants were also central. In Israel, starch grains on basalt tools show consumption of acorns, grasses, water chestnuts, and legumes as far back as 780,000 years ago. At Klasies River Cave, evidence from 120,000 years ago demonstrates cooked geophytes—tubers and rhizomes—alongside shellfish and meat, highlighting reliable, year-round carbohydrate sources.

These findings reveal that prehistoric diets were flexible, opportunistic, and regionally varied. Far from a single “Paleo diet,” early humans adapted to what was available, combining meat, plants, and coastal resources to meet their nutritional needs. Their survival depended less on scarcity and more on ingenuity, planning, and adaptability.

Homes, Campfires, and the Axis Mundi

By 100,000 years ago, fire was central to early Homo sapiens’ daily lives, shaping not just survival but thought, planning, and social organization. Archaeological sites show layers of ash, charred bones, and heat-treated stone, evidence that fire made food safer and more digestible, pushed back predators, and enabled migration into colder regions. Controlling fire required skill: gathering fuel, protecting embers, and anticipating needs—activities demanding foresight and experimentation.

Fire also transformed social life. Studies of modern hunter-gatherers, like the !Kung Bushmen of Namibia and Botswana, reveal that firelight changes how people interact. Daytime conversations often focus on practical matters or disputes, but nighttime discussions around the hearth are dominated by storytelling—imaginative, humorous, and relational. These fires created a social “niche,” building trust, transmitting knowledge, teaching rules, airing conflicts, and connecting dispersed networks. In essence, the campfire acted as an information hub, enabling cooperation and the spread of culture.

Religious historian Mircea Eliade described sacred points, or axis mundi, as centers where communities anchor themselves spiritually. For early humans, the campfire functioned similarly. It was a physical and symbolic center, a place of safety, warmth, ritual, and storytelling. As groups moved, lighting a new fire recreated that sense of order and belonging. For these nomadic peoples, “home” was less a fixed location than a fluid social and spiritual space anchored by fire—a luminous center of human life in a dark, unpredictable world.

Were they religious?

Reconstructing the spirituality of early Homo sapiens is challenging because beliefs don’t fossilize. Yet indirect evidence points to proto-religious practices by 100,000 years ago. One key line comes from burials. At Qafzeh Cave in Israel, humans were intentionally interred in carefully dug pits, often in flexed positions, with their heads oriented consistently. Grave goods—red ochre, tools, and animal bones—accompanied the deceased, including engraved Levallois cores and a deer antler placed on a child’s chest. These deliberate actions suggest ritual behavior and concern for the dead, hinting at early religious thought.

Symbolic artifacts provide another clue. At Bizmoune Cave in Morocco, marine shells were collected from distant sources, perforated, stained with red ochre, and worn as beads. The repeated use of specific shells and designs implies shared symbolic meaning, a prerequisite for social cohesion and perhaps belief systems.

A broader perspective comes from animism, the belief that plants, animals, and natural forces possess spirits. While 19th-century anthropologists framed it as the first stage in a linear religious evolution, today we recognize animism as a diverse, adaptive worldview. Indigenous cultures worldwide—from the Ojibwe and Ainu to Aboriginal Australians—treat animals, plants, and landscapes as sentient beings. Given its universality, animism may reflect the spiritual perspective of humans 100,000 years ago: a shared, symbolic understanding of the world beyond mere survival.

So as we can see, the human mind was equally complex and beautiful 100,000 years ago as it is today. Our species has come a long way since then, but never forget, we are still Homo sapiens.

Sources:

[1] Schoenemann, PT. 2006. “Evolution of the Size and Functional Areas of the Human Brain.” Annual Review of Anthropology 35(1).

[2] Lewis, J., and Harmand, S. 2016. “An earlier origin for stone tool making: implications for cognitive evolution and the transition to Homo.” Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371(1698):20150233.

[3] Wilkins, J. 2020. “Learner-driven innovation in the stone tool technology of early Homo sapiens.” Evolutionary Human Sciences 2:e40.

[4] Cordain, Loren, et al. 1999. “Scant evidence of periodic starvation among hunter-gatherers.” Diabetologia 42(3):383-4.

[5] Berbesque, J.C., et al. 2014. “Hunter–gatherers have less famine than agriculturalists.” Biology Letters 10:20130853.

[6] Marean, C., et al. 2007. “Early human use of marine resources and pigment in South Africa during the Middle Pleistocene.” Nature 449:905–908.

[7] Henshilwood, C., et al. 2011. “Taphonomic analysis of the Middle Stone Age larger mammal faunal assemblage from Blombos Cave, southern Cape, South Africa.” Journal of Human Evolution 60:746-767.

[8] Ahituv, H., et al. 2025. “Starch-rich plant foods 780,000 y ago: Evidence from Acheulian percussive stone tools.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 122(3):e2418661121

[9] Larbey, C., et al. 2019. “Cooked starchy food in hearths ca. 120 kya and 65 kya (MIS 5e and MIS 4) from Klasies River Cave, South Africa.” J Hum Evol. 131:210-227.

[10] Wiessner, Polly. 2014. “Embers of society: Firelight talk among the Ju/'hoansi Bushmen.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111(39):14027-14035.

[11] Eliade, M. 1957. Sacred and Profane: The Nature of Religion. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York.

[12] Bar-Yosef Mayer, D., et al. 2009. “Shells and ochre in Middle Paleolithic Qafzeh Cave, Israel: indications for modern behavior.” J Hum Evol. 56(3):307-14.

[13] Hovers, E, et al.. 1997. “A Middle Palaeolithic engraved artifact from Qafzeh Cave, Israel.” Rock Art Research 14(2):79-87.

[14] Shea, J. 2003. “The Middle Paleolithic of the East Mediterranean Levant.” Journal of World Prehistory 17(4):313–394.

[15] Sehasseh, E., et al. 2021. “Early Middle Stone Age personal ornaments from Bizmoune Cave, Essaouira, Morocco.” Sci Adv. 7(39):eabi8620.