What Archaeologists Still Can’t Explain About The Americas

Jun 09, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

Across the Americas, there are unexplained mysteries. Stones older than the stories explaining their origins—cut with impossible precision, aligned to stars, and carved by civilizations we still barely understand.

How were the massive stones of Pumapunku shaped so precisely without metal tools, for example? How did the Olmec manage to scatter their giant heads miles from any known quarry? Why did ancient artists in Peru draw geoglyphs the size of skyscrapers into the desert floor, seemingly only visible from the sky? The questions are endless.

And those are just the unmistakable monuments in plain sight. Genetic evidence now suggests a shocking link between ancient South Americans and the inhabitants of Australia and Oceania thousands of miles across the open ocean. Meanwhile, archaeologists are still debating the true timeline of human arrival in the Americas. Some evidence hints it happened tens of thousands of years earlier than we thought.

These aren’t just fringe theories, though there are those too. These are peer-reviewed puzzles—and they’re reshaping what we thought we knew about pre-Columbian history. Archaeologists have pieced together much of the past, but in certain places, the trail goes cold. In this video, we’re taking that trail to see where it leads, where archaeology has yet to account for some of America’s most profound and meaningful mysteries.

Let’s start in South America

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Megalithic Construction

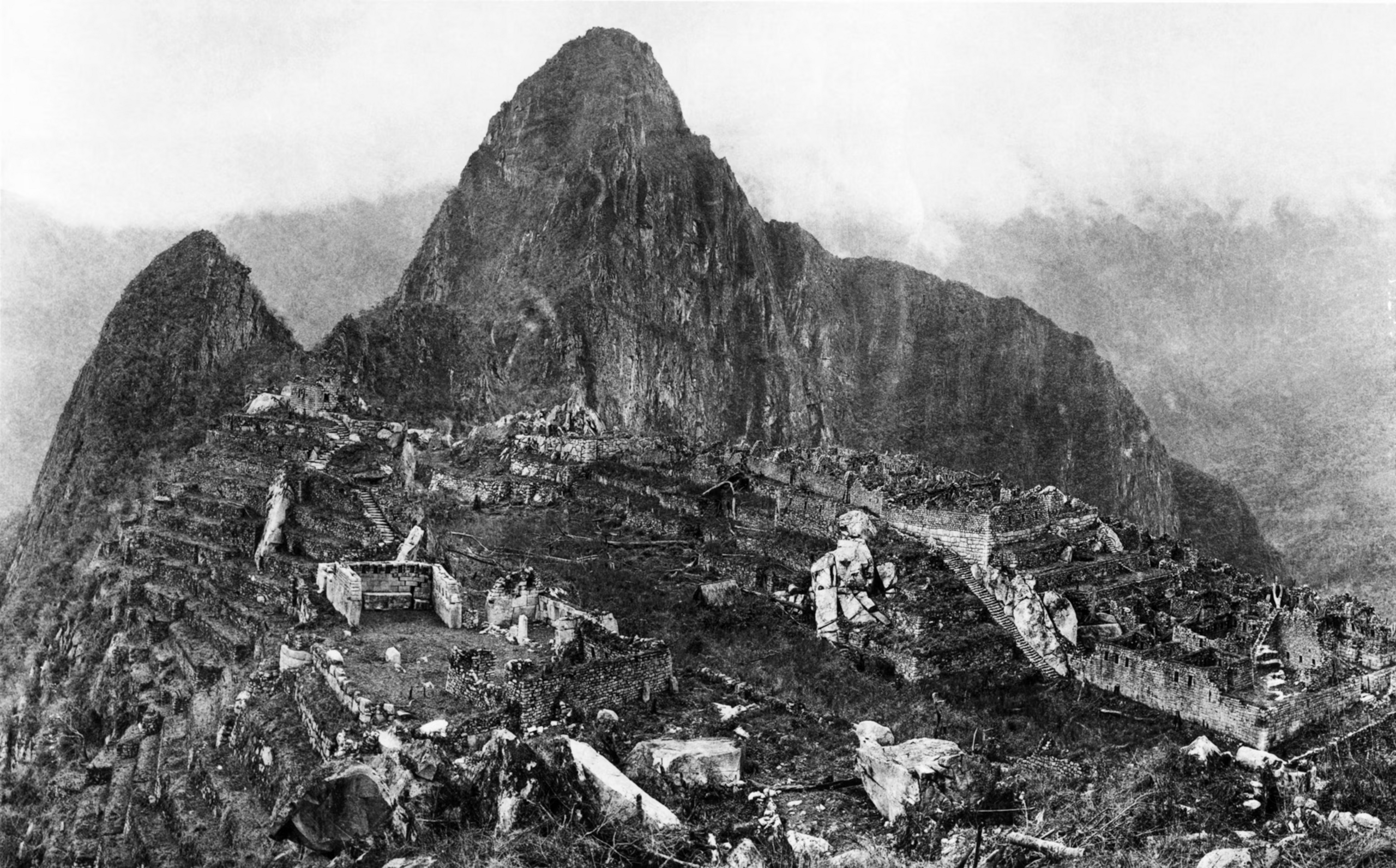

When it comes to ancient American architecture, Machu Picchu often steals the spotlight—but the real mystery lies in how it was built. The site’s massive granite blocks, precisely interlocked without mortar or metal tools, showcase Inca engineering that modern experts still struggle to fully explain. Even more puzzling, some of these Inca structures rest on older, rougher stone foundations—suggesting different phases of construction, or perhaps even earlier cultures entirely.

Sites like Pumapunku and Tiwanaku in Bolivia push the enigma further. At Pumapunku, perfectly shaped stone blocks, identical in size and alignment, hint at prefabrication and advanced planning—without any known tools or workshop remains to support it. Tiwanaku’s builders went even further, using copper-alloy clamps and intricate drill holes to create a level of stone precision rivaling modern machines. Despite centuries of excavation, we still don’t know how they did it.

Then there’s the Olmec colossal heads—50-ton basalt sculptures transported without wheels. While fringe theories attribute them to ancient African contact, no credible archaeological evidence supports this. What remains clear is that Indigenous American civilizations achieved stunning architectural feats with methods we’ve yet to fully uncover. These stones may be silent, but their mysteries are loud and unresolved.

Geoglyphs - The Nazca Lines

Photo by: Diego Delso