These Stone Age Weapons Were Made From Fossils

Jul 14, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

When I was a kid, I dreamed of becoming a paleontologist. It’s the first career path I really remember obsessing over. I can remember visiting places like the Museum of Natural History, where my parents would buy me these toy paleontology kits. They were little balls of sand with hidden dinosaur fossils and excavation tools. Even though I knew they were fake, the feeling of discovery was real.

Today, I’m an archaeologist. Clearly that sense of discovery has not gone away. Though they aren’t exactly the same thing, there is some crossover between the two fields. None is clearer than what I’ll be sharing with you in this video.

Humans and our ancestors have been creating tools for about 3 million years. They range from crudely smashed Oldowan cores to the finely crafted arrowheads of the Upper Paleolithic. After years of experimentation, we’ve discovered the ideal stone materials for creating such tools. What’s interesting is that these materials are often composed of tiny fossils from ancient organisms. Less common are artifacts embedded with fossils large enough to see with the naked eye.

These tools are layered with even more history than we think. When early humans picked up a chunk of flint to shape into a blade, they were unknowingly reaching into a much deeper past. A past filled with microscopic sea creatures and ancient corals. In rare cases, they even knapped around visible fossils. This has left us with tools that double as windows into Earth’s distant biological history. In the beautiful intersection of geology, paleontology, and archaeology, we can uncover how some of the earliest tools ever made are literally built from the remains of prehistoric life.

To watch the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Macrofossils

West Tofts Acheulean Handaxe

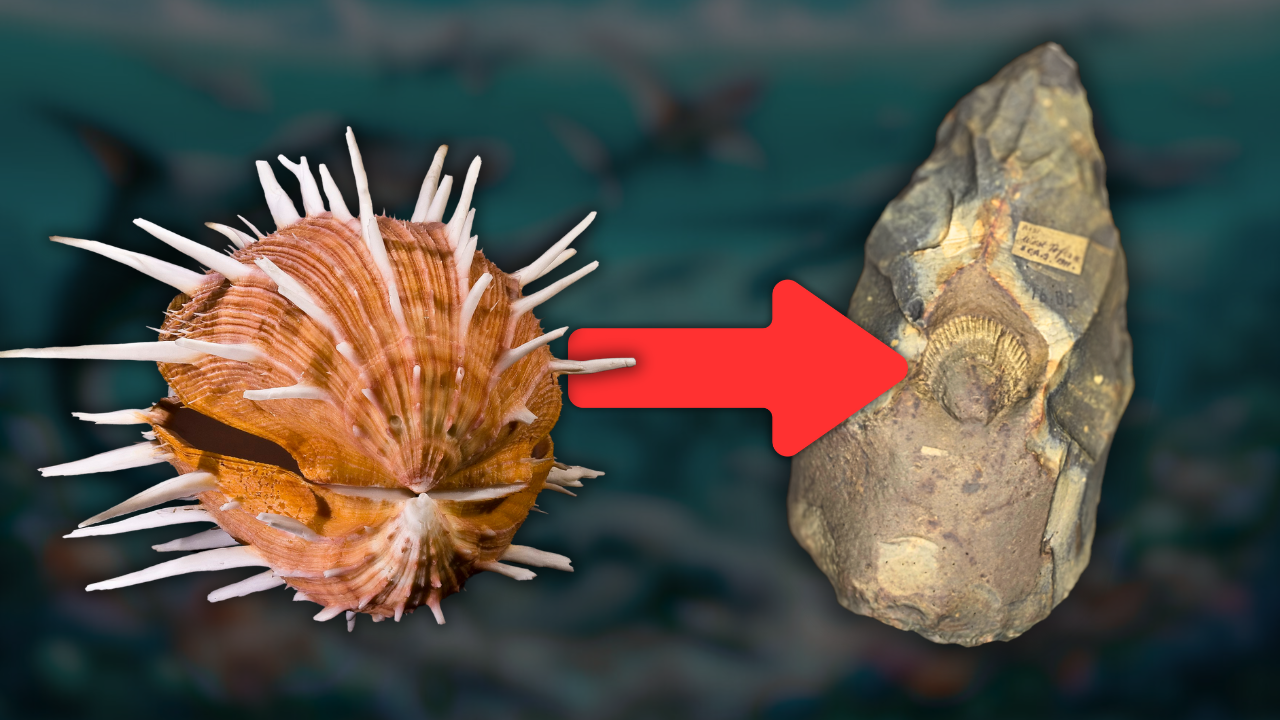

Some of the clearest examples of the overlap between archaeology, geology, and paleontology are stone tools that actually contain visible fossils. These “macrofossils” don’t need microscopes to spot—unlike microfossils, which are under 0.1 mm and require magnification.

A standout example is the West Tofts Acheulean handaxe from Norfolk, England, dating to the Lower Paleolithic (500,000–300,000 years ago). Crafted by archaic humans like Homo heidelbergensis, it’s made from flint containing a large, fossilized Cretaceous bivalve—Spondylus spinosus. This spiny oyster lived 80–100 million years ago in warm, shallow seas, attaching to rocks and filtering plankton. Its tough, spiny shell fossilized beautifully in Europe’s chalk and flint beds, forming nodules that early humans later shaped into tools.

The fossil’s perfect placement at the center of the handaxe face is striking. Some scholars argue this was intentional, suggesting an aesthetic choice to preserve the fossil while knapping. Others see it as chance selection. Regardless, it’s a rare, remarkable artifact that links human craft to ancient marine life.

Another famous example is the Swanscombe Handaxe from Kent. Found in Thames Valley gravels dating to the Hoxnian Interglacial (~400,000 years ago), it features a prominent echinoid fossil (a type of sea urchin) embedded in the flint. Echinoids like Conulus evolved tough, star-patterned shells that fossilized well, especially in England’s Cretaceous chalk beds.

Other rarer finds include a circular scraper from France made from a fossilized sea urchin, and a Mousterian scraper from Germany bearing the imprint of a Devonian brachiopod.

These tools are exceptionally rare in the archaeological record—like finding a legendary Pokémon on your last throw. Did their makers choose fossil-rich nodules on purpose? Did they feel awe at these ancient remains?

We may never know for sure. But there is evidence that prehistoric people collected fossils deliberately. Finds include belemnites (squid-like cephalopods from the Mesozoic), snail-like gastropods, and even extinct rhino molars—brought to sites far from their original beds.

These discoveries suggest that our ancestors didn’t just use stone—they may have marveled at the ancient stories it held. In a way, they were the first fossil collectors, bridging human history with Earth’s deep past.

Microfossils

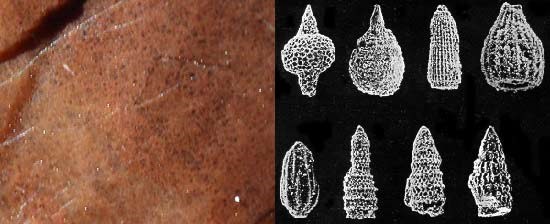

A magnified piece of chert showing radiolaria. Microscope image: USGS

Not all fossils in stone tools are easy to spot. Many of the rocks ancient humans favored—like chert and flint—are built from the microscopic remains of ancient life. Over millions of years, ocean floors collected thick layers of tiny organisms: radiolarians, diatoms, and sponges.

Radiolarians are single-celled plankton with intricate silica skeletons. When they died, their remains piled up on the seafloor and, under pressure, transformed into dense, glassy rock—often the dark-gray or black cherts prized for tools. Diatoms, their photosynthetic cousins, formed similar silica-rich layers in cooler, nutrient-rich waters, which also hardened into quality toolstone. Siliceous sponges added their rigid, lattice-like structures to the mix, further enriching these deposits.

Over time, these microscopic skeletons cemented into solid nodules and layers of rock. Tectonic uplift and erosion eventually exposed them at the surface, where early humans found them.

What makes these fossil-packed stones so special isn't just their ancient origin—it's their conchoidal fracture. As silica re-crystallized around these tiny fossils, it created an ultra-fine, glassy matrix that breaks in smooth, predictable curves. This let early toolmakers strike off sharp, reliable flakes with precision.

These rocks weren’t just hard—they were engineered by nature over eons to be perfect for shaping. Ancient people recognized that potential and learned how to unlock it, turning Earth's deep-time fossil record into essential survival technology.

Some Archaeological Sites

Burlington Chert projectile point.

It’s so fascinating to me to see how prehistoric people used these rocks in different places and times, and what those choices reveal about their lives.

In the American Midwest, Native Americans heavily relied on Burlington chert—a striking white chert often streaked with gray or brown and packed with crinoid fossils. Microscopic analysis reveals sponge spicules, brachiopods, and corals. Massive quarry sites in Missouri show where people mined and shaped blanks before carrying them across vast distances. From Illinois to Mississippi, Burlington chert fueled trade and toolmaking.

Out west, Native Californians used Monterey chert, a fine-grained, glassy material formed from ancient diatoms and sponges. Found in places like Claremont Canyon and the cliffs near Pismo, it offered sharp, beautiful toolstone for coastal communities.

In Europe, Neolithic groups mined Cretaceous flint from chalk beds rich in fossil sea urchins and sponges. At Grime’s Graves in England, they dug deep shafts to extract it—an enormous effort that likely carried spiritual weight. Archaeologists have found ceremonial pottery, carvings, and even a buried dog in abandoned shafts, suggesting these stones held more than just functional value.

When we study these sites, we’re not just cataloguing stone debris. We’re uncovering ancient knowledge systems, trade connections, and cultural affinities to the natural world. Fossil-rich toolstone connects us to deep time. To our ancient ancestors and the prehistoric life that even predates them.

Sources:

[1] Flanders, E. and Key, A. 2023. “The West Tofts handaxe: A remarkably average, structurally flawed, utilitarian biface.” Journal of Archaeological Science 160(4).

[2] Oakley, K. P. 1981. “Emergence of Higher Thought 3.0--0.2 Ma B.P.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 292(1057): 205–211.

[3] Echinoids - British Geological Survey

[4] McNamara, K. 2007. “Shepherds' crowns, fairy loaves and thunderstones: the mythology of fossil echinoids in England.” Geological Society, London, Special Publications 273(279-294).

[5] Hussain, S.T., and Will, M. 2021. “Materiality, Agency and Evolution of Lithic Technology: an Integrated Perspective for Palaeolithic Archaeology.” J Archaeol Method Theory 28(617-670).

[6] Bredekamp, H. 2019. “Art history and prehistoric art: rethinking their relationship in light of new observations.” The Gerson Lectures Foundation

[7] Moncel, M., et al. 2012. “Non utilitarian objects in the Palaeolithic : emergence of the sense of precious?” Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 401:24-40

[8] Burlington Chert

[10] Monterey Chert