The OLDEST Evidence of Seafaring Technology

Jun 16, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

Imagine staring across a vast, indifferent ocean with no land in sight. Your only companion is a hollowed log bobbing beneath your fingertips as waves smack against its side. Each sway feels like a gamble with fate: one wrong move, and the sea claims you.

This isn’t a story of conquistadors or steamships—it’s a tale of courage carved into prehistoric wood. Tens of thousands of years ago, our ancestors made crossings with the simplest of tools… No steam, no sail, no compass.

Today, we’re hunting for the first signs of humans traversing the high seas, from the world’s oldest dugout canoe found in a Dutch peat bog to mysterious footprints left on islands many kilometers offshore. Along the way, we’ll take a look at the artifacts and footprints that don’t necessarily give us direct evidence of open ocean navigation, but that can only be explained if people were capable enough to do so.

By the end of this voyage, you’ll see why seafaring wasn’t just travel—it was a revolutionary cognitive leap that connected continents and transformed our species. Let’s set sail into the deep history of human navigation and discover how the world’s first sailors challenged the unknown—and won.

This is the oldest evidence of seafaring technology.

To watch the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Archaeological Challenges

Turkish Museums

When it comes to uncovering ancient water travel, archaeologists rely on two kinds of evidence. The first is direct: physical remains of boats, paddles, or maritime tools. The second is inferred—clues like footprints, artifacts, or human remains found in places that couldn’t have been reached without crossing water. While both types are important, inferred evidence is more speculative and harder to prove. So let’s begin with the hard evidence.

The challenge? Boats were often made of wood, and wood rarely survives. Underwater environments can quickly destroy it—fungi, bacteria, and shipworms thrive in oxygen-rich waters, and even low-oxygen muds can become unstable over time. If preserved timbers are exposed too suddenly, they can crack, shrink, or disintegrate unless treated immediately. Add to that the physical abrasion of shifting sediments and currents, and it’s clear: much of the early seafaring record has likely been lost.

Still, a few remarkable sites have beaten the odds—places where the chemistry, temperature, and timing were just right. These rare “Goldilocks” zones of preservation have given us glimpses into early watercraft, and many of the best examples come from Europe.

The Hard Evidence

Long before Viking sails cut through the North Sea, Mesolithic peoples of north-central Europe and Scandinavia were already mastering the water. By around 4700 BC, hunter-gatherers along Denmark’s coasts and lakes relied on dugout canoes and hand-hewn paddles to move through reed-choked waters. One of the oldest known paddles, found in the Duvensee Moor in northern Germany, dates just before 4000 BC and was expertly carved from ash or oak. Similar finds in submerged Danish sites—like Horsens Fjord and Tybrind Vig—reveal that these tools weren’t just functional: some were decorated with zigzags, circles, even heart shapes. These weren’t simple rafts. They were precision-engineered craft for navigating coastal networks and seasonal fishing grounds.

Further south, Africa gives us an even older discovery. The Dufuna canoe, buried deep in alluvial mud near the edge of the Sahara, dates to around 6450 BC. Hewn from a massive log of Afzelia africana, this 8.4-meter dugout is Africa’s oldest known boat. Its makers likely used stone tools to hollow it out, allowing them to move through seasonal rivers and marshes of the once-lush “Green Sahara.” For early West African communities, the canoe was not just for fishing—it was a vehicle for trade, migration, and resilience.

But the world’s oldest known canoe comes from the Netherlands. Found in a peat bog near Pesse, this small dugout dates back to around 8200–7600 BC. Though modest in size, it was no primitive trough. Experimental archaeology has shown that the Pesse canoe could float, steer, and carry a human through shallow waters. It shows that even 10,000 years ago, Mesolithic foragers were crafting boats with balance, buoyancy, and purpose in mind.

Taken together, these finds—from Denmark, Nigeria, and the Netherlands—paint a vivid picture of our ancestors’ ingenuity. They weren’t crossing oceans just yet, but they were building the tools and knowledge that would one day make that possible. And as we’ll see next, some may have taken that leap far earlier than we thought.

The Indirect Evidence

Adam Brumm et al., Oldest cave art found in Sulawesi.Sci. Adv.7,eabd4648(2021).

Not every archaeological site gives us a boat. Often, what survives are subtle hints—like fish bones, exotic tools, or cave art in places humans shouldn’t have been able to reach without crossing open water. When we find footprints, artifacts, or cultural remains on islands that were never connected to the mainland, we rely on inference: if there was no land bridge, they must have arrived by sea.

One of the clearest examples is the site of Jerimalai in East Timor. Around 42,000 years ago, people were fishing in deep waters far beyond the reef, catching species like tuna and mackerel that can’t be accessed from shore. Later, they crafted delicate fishhooks from shell—among the oldest in the world. These finds strongly suggest that Timor’s early residents had small seagoing vessels, likely dugouts or lash-together rafts, and the planning skills to use them.

In Sulawesi, cave art adds another layer of evidence. The island has never been connected to mainland Asia, yet its limestone caves hold some of the world’s oldest paintings—like the 51,000-year-old narrative panel at Leang Karampuang. These weren’t isolated visits. Nearby sites such as Leang Tedongnge and Leang Bulu Sipong 4 feature large-scale animal figures and hunting scenes dating to 45,000 years ago and earlier. To reach Sulawesi, people had to cross straits more than 70 km wide—impossible without some form of watercraft and shared knowledge of navigation.

Farther south, the story culminates in Australia. The continent was never linked to Asia by land, and yet we find archaeological sites there dating back to at least 50,000 years ago—and possibly as early as 65,000. The most debated of these is Madjedbebe, a rock shelter in Arnhem Land with a deep sequence of stone tools, ochre, and hearths. Some scientists challenge the oldest dates, suggesting termites disturbed the soil, but the overall evidence supports human presence by 50 ka. The only plausible route? A series of sea crossings across Wallacea, including one over 100 kilometers long.

Together, these finds—from Timor to Sulawesi to Australia—form a powerful case for early seafaring. Even if the boats themselves are gone, the evidence they leave behind is scattered across islands and caves, etched into shell, pigment, and bone. And these feats weren’t limited to Homo sapiens. In the next section, we’ll ask: could other, now-extinct human species—like Neanderthals or Homo floresiensis—have taken to the sea as well? Let’s explore the possibilities.

Seafaring Before Homo Sapiens

Gómez-Robles, A. The dawn of Homo floresiensis. Nature 534, 188–189 (2016).

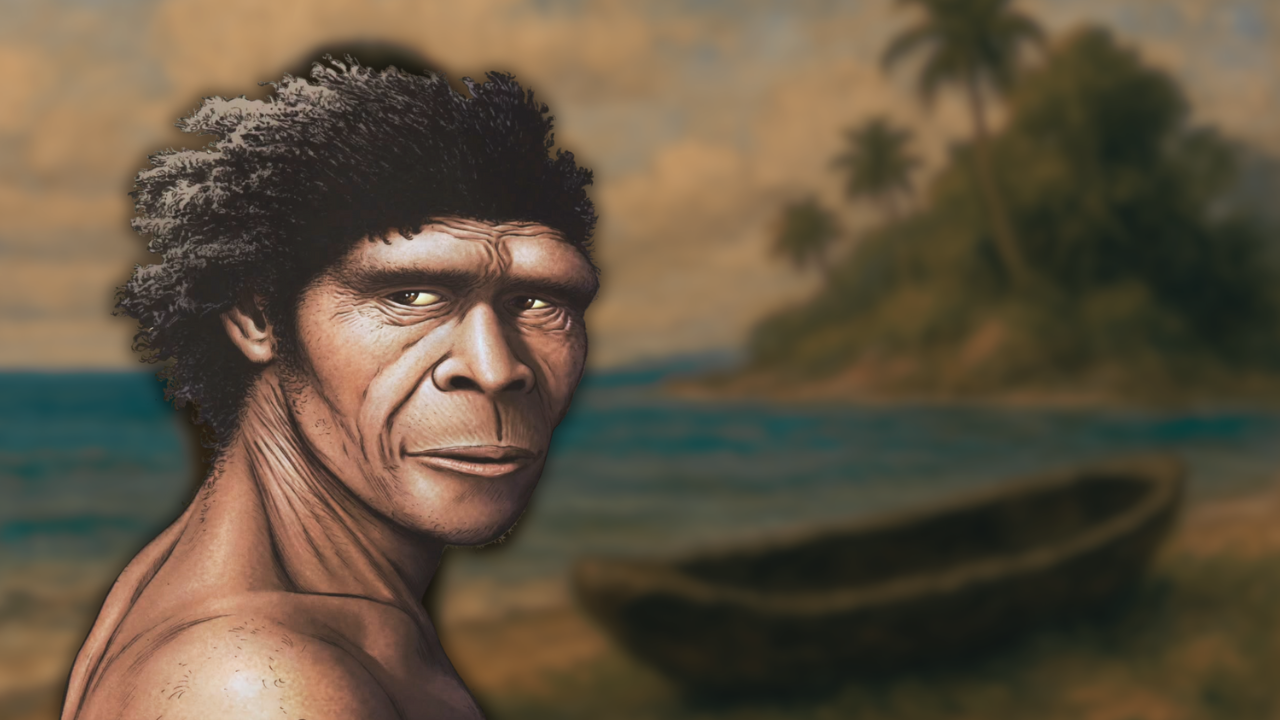

Long before Homo sapiens built boats or mapped coastlines, other human species may have already braved the sea—deliberately or otherwise.

On the island of Crete, archaeologists have unearthed large cutting tools like hand-axes and cleavers dating between 130,000 and 113,000 years ago. Found on the Plakias peninsula, these artifacts sit atop ancient marine terraces, and resemble the Acheulean technology once used by Homo erectus or H. heidelbergensis. Since Crete has been isolated by at least 40 km of open Mediterranean water since the Miocene, the toolmakers could only have arrived by sea. While some argue this journey might have been accidental, the density and clustering of artifacts suggest repeated visits by hominins who understood both the coastline and how to navigate it.

Even more surprising is what researchers found on the Indonesian island of Flores: the remains of Homo floresiensis, a tiny human species nicknamed the “hobbit.” Standing just over a meter tall, these hominins likely evolved from earlier Homo erectus populations that became isolated and underwent island dwarfism—a process where large species shrink over generations to survive with fewer resources. Stone tools on Flores date back nearly one million years, and H. floresiensis may have survived until as recently as 12,000 years ago.

But how did they get there? Flores, like Crete, has never been connected to the mainland. Most researchers believe their ancestors arrived by crossing ocean channels, but not through advanced seafaring. Instead, a leading theory suggests they may have been swept out to sea by natural disasters—tsunamis or storms—clinging to rafts of vegetation. Such accidental ocean crossings, while rare, are not unheard of: green iguanas rafted to Anguilla in 1995, and primates are thought to have crossed the Atlantic from Africa to South America some 35 million years ago.

While we can't say these early hominins were building boats, the archaeological evidence points to something just as remarkable: even without sails, compasses, or intention, ancient humans—and their cousins—found ways to reach the unreachable.

Sources:

Sources:

[2] Bokelmann, K. 2012. “Spade paddling on a Mesolithic lake – Remarks on Preboreal and Boreal sites from Duvensee (Northern Germany)”. In Niekus, M.J.L.Th.; Barton, R.N.E.; Street, M.; Terberger, Th. (eds.). A Mind Set on Flint: Studies in Honour of Dick Stapert. Elde: Barkhuis. pp. 369–380.

[3] Skriver, Claus, and Per Borup. 2012. “The Paddle Oars from Horsens Fjord.” Skalk: News on the Past, 4: 3–7.

[4] Malm, T. 1995. “Excavating Submerged Stone Age Sites in Denmark – The Tybrind Vig Example.” In Man and Sea in the Mesolithic, edited by Anders Fischer, 263–296. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

[5] Garba, A. 1996. “The architecture and chemistry of a dug-out: the Dufuna Canoe in ethno-archaeological perspective.” Berichte des Sonderforschungsbereichs. 268(8):193.

[6] Gumnior, Maren and Thiemeyer, Heinrich. 2003. “Holocene fluvial dynamics in the NE Nigerian Savanna.” Quaternary International 111: 54.

[7] Breunig, P., et al. 1996. “New research on the Holocene settlement and environment of the Chad Basin in Nigeria.” African Archaeological Review 13(2):116–117.

[8] Langley M, et al. 2016. “42,000-year-old worked and pigment-stained Nautilus shell from Jerimalai (Timor-Leste): Evidence for an early coastal adaptation in ISEA.” J Hum Evol. 97:1-16.

[9] O’Connor, S., et al. 2011. “Pelagic Fishing at 42,000 Years Before the Present and the Maritime Skills of Modern Humans.” Science 334,1117-1121.

[10] Oktaviana, A.A., et al. 2024. “Narrative cave art in Indonesia by 51,200 years ago.” Nature 631, 814–818.

[11] 45,000-Year-Old Pig Painting in Indonesia May Be Oldest Known Animal Art

[12] Aubert, M., et al. 2019. “Earliest hunting scene in prehistoric art.” Nature 576, 442–445.

[13] Clarkson, C., et al. 2017. “Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago.” Nature 547, 306–310.

[14] Hayes, E.H., et al. 2022. “65,000-years of continuous grinding stone use at Madjedbebe, Northern Australia.” Sci Rep 12, 11747.

[15] Runnels, C., et al. 2014. “Lower Palaeolithic artifacts from Plakias, Crete: Implications for hominin dispersals.” Eurasian Prehistory 11(1-2):129-152

[16] Lawler, Andrew. 2018. “Neandertals, Stone Age people may have voyaged the Mediterranean.” Science.

[17] Dennell, R., et al. 2014. “The origins and persistence of Homo floresiensis on Flores: biogeographical and ecological perspectives.” Quaternary Science Reviews 96, 98-107.

[18] Brumm, A., et al. 2010. “Hominins on Flores, Indonesia, by one million years ago.” Nature 464, 748–752.

[20] Van den Bergh, G., et al. 2022. “An integrative geochronological framework for the Pleistocene So'a basin (Flores, Indonesia), and its implications for faunal turnover and hominin arrival.” Quaternary Science Reviews 294, 107721