The OLDEST Buildings On Every Continent

Jan 12, 2026

By: Greg Schmalzel

Most of western society has been built around the architecture of the Greeks and the Romans. Despite the beauty and grandeur of these ancient structures, there are much older buildings scattered around the world. How much older? In some cases, many thousands of years. They speak to the hands of craftsmen whose stories are seldom told.

These buildings weren’t designed to impress future tourists or the archaeologists who eventually discovered them. They are expressions of extinct cultures. Many were built by small communities, or by people who hadn’t yet invented agriculture, writing, or metal tools. Some were made of stone. Others of wood, bone, or earth - materials that usually vanish with time. What survives, does so by chance. And what we call the “oldest” buildings are really the rare moments when human intention outlasted decay. All together, they form a fragmented but powerful record of when people first began shaping the world we see around us - the built environment.

These are the oldest buildings on every continent.

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

What is a Building?

What is a building? It sounds simple: walls, a roof, maybe a door. But archaeologically, those features rarely survive in full. Often, all we find are stones, soil stains, or postholes. We must infer the rest. Also, different cultures have defined buildings differently. For example, what looks incomplete to us may have been complete to them.

For this video, a building is defined by intention. Humans deliberately shape materials and space, whether stacking stones, shaping wood, or rearranging the landscape. Early buildings were often temporary. Sometimes they weren’t homes at all, but markers, gathering places, or ritual spaces. What survives of them does so by chance, and every once in a while we score.

So with this in mind, let’s dive into continent number one - South America.

South America

Caral-Supe by Paulo JC Nogueira

The Americas stretch from Arctic tundra to tropical rainforest, spanning two continents largely isolated from the rest of the world. This north–south geography shaped how and when humans arrived. During periods of low sea level, a land bridge called Beringia connected Siberia and Alaska. People likely crossed it on foot, but coastal routes along the Pacific—possibly using boats—may have been just as important.

Archaeology keeps pushing the timeline back. Footprints at White Sands, New Mexico, now suggest people were present by 20,000 years ago. Earlier still, Monte Verde in southern Chile challenged older models with dates over 14,000 years ago. What makes Monte Verde extraordinary is not just its age, but its architecture. A community of roughly 20–30 people built a long, rectangular wooden hut nearly 20 meters long. Waterlogged conditions preserved its wooden foundations, vertical posts, animal-hide walls, and internal room divisions. Inside were clay-lined hearths, food remains, and even a human footprint frozen in time. Nearby, a second wishbone-shaped structure built on an imported gravel foundation contained medicinal plants and butchered mastodon bones, suggesting specialized use. Together, these represent the oldest known buildings in South America.

Thousands of years later, architecture in the region became monumental. In Peru, Sechín Bajo—dating to at least 3500 BCE—features stone-and-adobe platforms, sunken circular plazas, stairways, and layered construction phases. An early adobe frieze depicts a human-like figure holding symbolic objects, hinting at ritual and ideology. Caral-Supe, appearing 500–1000 years later, expanded this tradition into a true urban center with massive stepped pyramids, plazas, and residential zones. Though these sites didn’t directly shape later civilizations, their core architectural ideas—platforms, plazas, and ritual spaces—would echo across the Americas for millennia.

North America

Watson Brake by Herb Roe

South America preserves some of the world’s earliest stone buildings, but north of the equator the story unfolds very differently. In early North America, architecture was rare, small, and highly perishable. The earliest hunter-gatherers likely built shelters similar to those at Monte Verde, but few survive. One exception is the Mountaineer Site in Colorado, associated with the Folsom culture around 10,000 years ago. There, archaeologists found a shallow circular house basin ringed with stones, along with daub bearing impressions of wooden poles. Postholes, hearths, and stone tools suggest a temporary hunting camp positioned to overlook a river valley.

Permanent construction in North America followed a different path than in South America. Stone was rarely used. Instead, people shaped the landscape itself. By around 3500 BCE, hunter-gatherers in Louisiana were building large earthen monuments at Watson Brake, the oldest known mound complex on the continent. The site consists of 11 mounds connected by ridges, forming an oval around a large central space. Construction began over midden deposits—dense layers of refuse containing charcoal, stone debris, burned clay, and animal remains. These middens were deliberately reused as structural fill, providing stability and symbolic foundations. Building continued in stages for centuries, yet the central area was kept clear, suggesting ceremonial use rather than habitation.

True domestic architecture appears later. Around 500 BCE, Basketmaker II communities in the American Southwest began building permanent homes. These included circular surface structures in some regions and semi-subterranean pithouses in others. Dug into the ground and reinforced with posts, earth, and adobe, pithouses had hearths, ventilation features, and storage pits. Unlike earlier camps, these homes were reused over generations, marking a shift toward permanence and settled life.

Europe

Dolní Věstonice Museum

Human migration into the Americas was relatively recent and involved only Homo sapiens. Europe tells a different story. Here, the oldest buildings force us to ask whether other human species also built structures. The answer comes from Bruniquel Cave in France.

Deep inside the cave, more than 330 meters from the entrance, archaeologists discovered ring-shaped structures built by Neanderthals around 176,500 years ago. Neanderthals deliberately broke stalagmites, stacked them into two large rings and four smaller piles, and reinforced them with vertical supports. About 400 pieces were used, weighing over two tons. Traces of fire appear on every structure, showing controlled use of flames in complete darkness. The cave was too deep for shelter, suggesting ritual, social, or technical purposes. Bruniquel proves Neanderthals could plan, organize labor, and modify environments on a large scale.

The oldest surviving above-ground building made by Homo sapiens in Europe is the Cairn of Barnenez, also in France. Built between 4500 and 3900 BCE, it is a massive stone funerary monument overlooking the Bay of Morlaix in Brittany. The cairn stretches 75 meters long and contains eleven passage tombs. It was built in two phases using dolerite and later granite, with corbelled stone chambers that remain structurally sound after six millennia. Many stones bear symbolic carvings.

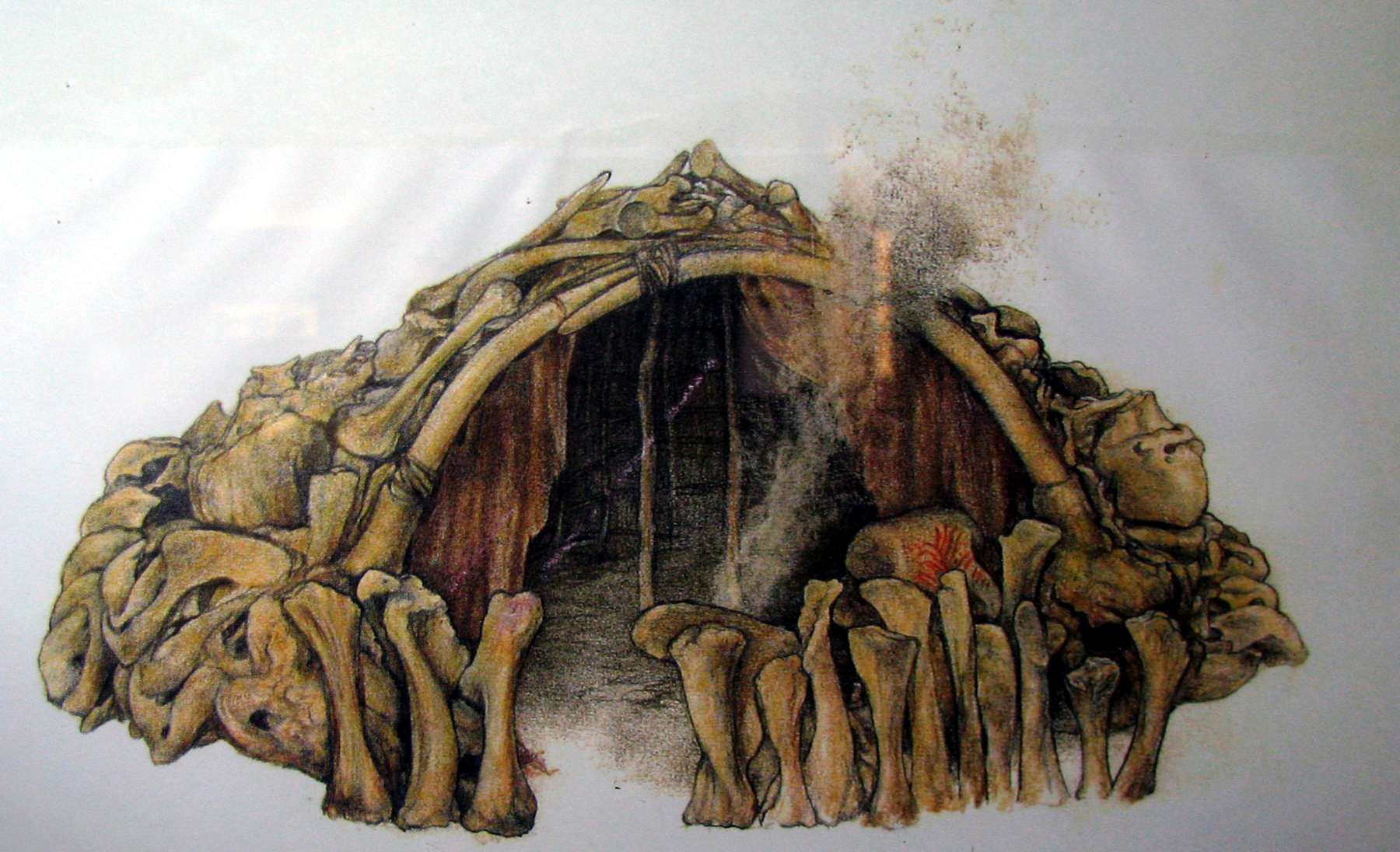

Older still—but rarely preserved—are mammoth-bone huts from Ice Age Europe. Dating from 26,000 to 14,000 years ago, these free-standing circular shelters were built from skulls, tusks, and bones scavenged from long-dead mammoths. Together, these structures show that long before cities, Europeans were already experimenting with durable, purpose-built architecture.

Asia

Hōryū-ji Temple

As we move into Asia, we encounter the oldest known megalithic structures on Earth: Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe in southeastern Turkey. Dating to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic around 9600 BCE, neither site shows evidence of houses or daily domestic life. Instead, they consist of monumental communal architecture.

Göbekli Tepe is defined by circular and oval limestone enclosures, 10–30 meters wide, built from carefully set T-shaped pillars. Some stand over five meters tall. Two central pillars dominate each enclosure, surrounded by smaller ones linked by dry-stone walls. Many are carved with animals, abstract symbols, and human-like forms, suggesting symbolic or ritual use.

Karahan Tepe follows the same tradition but integrates architecture directly into the bedrock. Pillars often rise from the ground itself. One subterranean space, known as Structure AB, contains ten phallus-shaped pillars carved in place, plus one imported pillar, alongside a carved human head overlooking the chamber. Its meaning remains unknown, highlighting how little we truly understand these sites.

East Asia lacks structures this old, but Japan preserves the oldest surviving wooden buildings at Hōryū-ji Temple. Founded in 607 CE, the complex blends Korean and Chinese influences. Its five-story pagoda and Golden Hall use a post-and-beam timber system, wide tiled roofs, and a seismic-resistant central pillar. Despite fires and earthquakes, careful restoration and traditional carpentry have allowed Hōryū-ji to endure, making it a rare survivor of early wooden architecture.

Australia

Peter Gouldthorpe

Australia continues the pattern of perishable Indigenous architecture. Before European colonization, Aboriginal Australians built shelters from organic materials suited to local environments rather than permanence. In Tasmania (lutruwita), the best evidence comes from hut depressions. These mark beehive-shaped dwellings made from bent wooden poles, often tea tree, and covered with bark. Some may have used whale ribs for support. The huts housed six to fourteen people and featured small entrances and central hearths. Many were built near coasts and estuaries, close to food-rich zones, and sometimes clustered into small villages. Though the structures decayed, the depressions preserve charcoal, shell, bone, and tools, revealing long-term lifeways.

By contrast, Australia’s oldest surviving European building is Elizabeth Farm Cottage in New South Wales. Built in 1793, it began as a simple four-room brick house and was expanded over time. Its layered construction reflects the gradual shift from early colonial building methods to more permanent architecture—leading us to the final continent, where human history begins much later.

Antarctica

Canterbury Museum

For most of human history, Antarctica was a frozen no-man’s land. Claims of much earlier human contact often point to historical maps. The Piri Reis map of 1513 is sometimes said to show an ice-free Antarctic coast, while the Oronteus Finaeus map of 1531 depicts a large southern continent with rivers and mountains. The Philippe Buache map of 1739 even shows Antarctica split by an inland sea. However, mainstream scholars agree these features reflect speculation, misidentified coastlines, and Renaissance geographic guesswork—not ancient exploration.

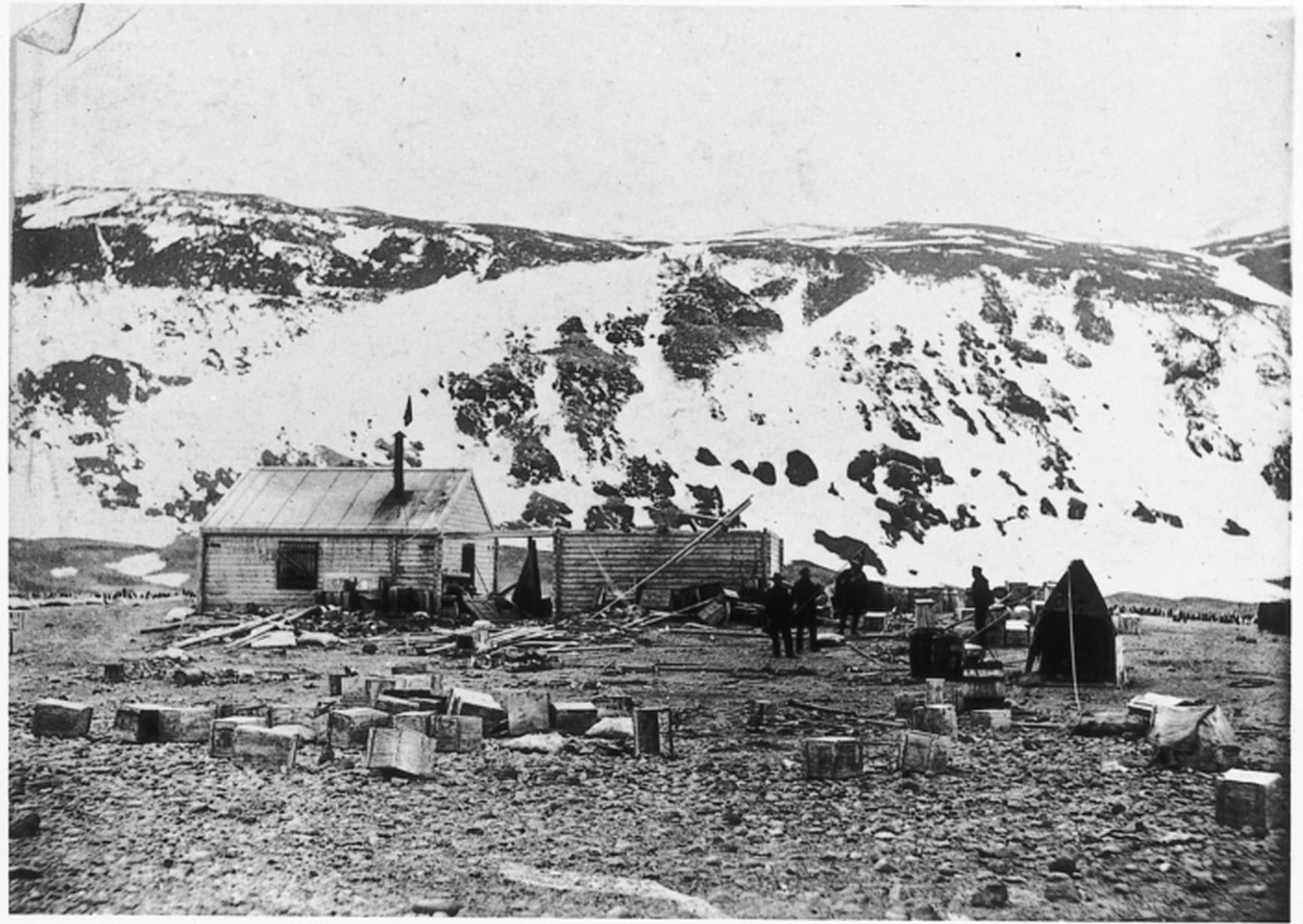

The first widely accepted human encounters with Antarctica occurred in the early nineteenth century, during the age of polar exploration. In 1820, multiple expeditions from Russia, Britain, and the United States independently sighted the continent. The first likely landing followed in February 1821, when American sealer John Davis reportedly stepped ashore on the Antarctic Peninsula. While debated, this remains the earliest credible evidence of a human setting foot on Antarctica.

The continent’s oldest surviving buildings are the wooden huts at Cape Adare, constructed in 1899 during the British Antarctic Expedition led by Carsten Borchgrevink. Built from prefabricated timber, they served as living quarters, storage, and workspaces. Preserved by the cold, they represent humanity’s first enduring architecture on Earth’s most extreme continent.

Sources:

[1] Pino, M., and Dillehay, T. 2023. “Monte Verde II: an assessment of new radiocarbon dates and their sedimentological context.” Antiquity 97(393):524-540.

[2] Fuches, P., et al. 2009. “Del Arcaico Tardío al Formativo Temprano: las investigaciones en Sechín bajo, valle de Casma.” Boletín de Arqueología PUCP

[3] Pringle, H. 2001. “The First Urban Center in the Americas.” Science 292,621-621.

[4] Mountaineer Site

[5] Stiger, M. 2006. “A Folsom Structure in the Colorado Mountains,” American Antiquity 71, 2.

[6] Stringer, G. 2005. “Watson Brake, a Middle Archaic Mound Complex In Northeast Louisiana.” American Antiquity 70(4):631-668.

[7] Lipe, W. “BASKETMAKER II (1000 B.C.-A.D. 500)”

[8] Jaubert, J., et al. “Early Neanderthal constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France.” Nature 534, 111–114 (2016).

[9] The Great Cairn of Barnenez

[10] Rey-Iglesia, A. 2024. “Ancient biomolecular analysis of 39 mammoth individuals from Kostenki 11-Ia elucidates Upper Palaeolithic human resource use.” Quaternary Environments and Humans 3(6):100049.

[11] Schmidt, K. 2011. “Göbekli Tepe - The Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs.” Documenta Praehistorica 37:239.

[12] Karul, N. 2021. “Buried Buildings at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Karahantepe.” Türk Arkeoloji Ve Etnografya Dergisi (82), 21-31.

[13] Buddhist Monuments in the Horyu-ji Area

[14] Barham, L., et al. 2023. “Evidence for the earliest structural use of wood at least 476,000 years ago.” Nature 622, 107-111.

[15] Snape, S. 2011. Ancient Egyptian Tombs: The Culture of Life and Death. Chichester, West Sussex, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

[16] Aboriginal hut depressions

[17] Elizabeth Farm House, 70 Alice St, Rosehill, NSW, Australia