The Killer Ape Theory of Human Evolution

Nov 24, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

Why are humans so prone to violence? Look around you and you’ll see no shortage of it. Turn on the news, and you’ll see war. Turn on social media, and you’ll find street fights. And if you’re so unfortunate, you may only need to step out your front door. Why are we like this?

It’s a question we’ve been asking ourselves for ages, and we haven’t yet come to a solid answer. Some theories claim it's in our nature - that we’re biologically hardwired for violence. Others claim that it's in our culture - that we’re entrained to be violent by our social groups. Both paths are supported by a fair amount of evidence, and they may both be true. But one theory claims that humans aren’t only violent by nature, but that it may have been the very key to our evolution - to what separated us from the rest of the primates. It’s aptly called the Killer Ape Theory, and its implications for human evolution are extreme. But what exactly does the theory argue and how accurate is it given what we know?

Let’s dive into these questions by exploring how it was born, the evidence that made it persuasive, and the detailed scientific work that might be dismantling it. Whether you think humans are born to fight or wired to cooperate, the true story is far more interesting - and it starts many, many years ago.

To watch the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Early Ideas About Human Violence

Humanity has spent thousands of years asking the same question: why are we violent? You can see this tension right at the start of the world’s most printed book. The first story of humans born from humans isn’t about creation or triumph. It’s about murder.

Cain kills Abel out of envy. The message is blunt. Violence isn’t just “out there.” It lives inside us. One act, two brothers, and a universal truth: humans have always wrestled with the darkness within.

Ancient China had the same debate. Mencius said people are born good, but corrupted by bad environments. Xunzi said the opposite. Humans are born chaotic and selfish, and only culture and discipline can restrain us. Two thinkers. Two visions of human nature.

Centuries later, the West revisited the same clash. Hobbes imagined a world without authority: a brutal “war of every man against every man.” Only strong governments keep chaos at bay. Rousseau disagreed. Humans were peaceful in nature, he said. Civilization—especially property—made us violent.

Then Darwin entered the conversation. His theory of natural selection reframed everything. If humans evolved like every other animal, then our behavior—violent or otherwise—must have evolutionary roots. In The Descent of Man, Darwin argued that bravery, loyalty, morality, and hunting skills all evolved because they helped us survive. Our hands became tools. Our tools became weapons. Our weapons made us dominant hunters.

Modern science has revised his ideas, but not erased them. New research still suggests that meat-eating, hunting, and endurance running played major roles in shaping who we are. The question remains: is violence a flaw… or part of our design?

The Killer Ape Theory

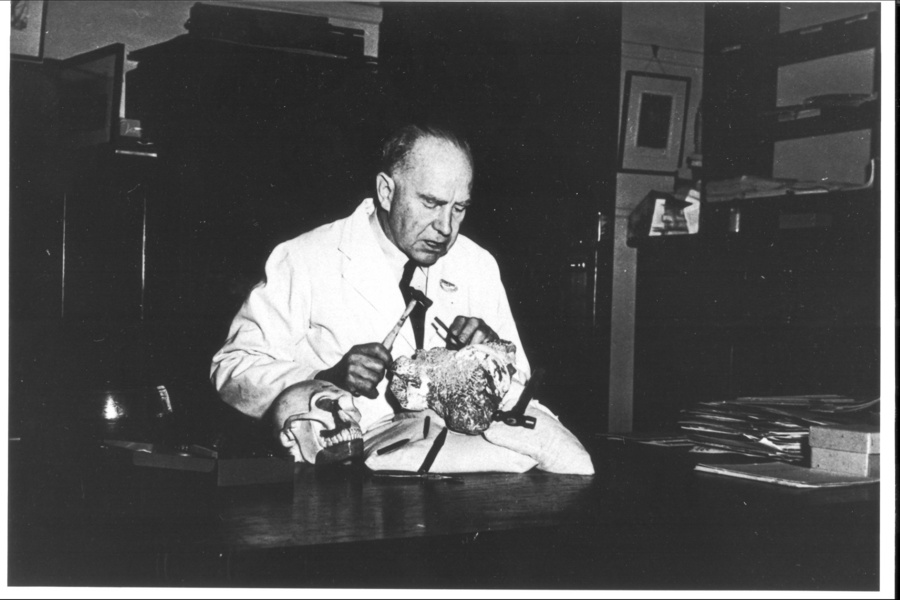

In the 1950s, anthropologist Raymond Dart pushed the idea of a violent human past to its limit. In his paper “The Predatory Transition From Ape to Man,” he argued that early hominins lived in a brutal world—and added to it with their own brutality. Dart believed Australopithecus africanus wasn’t a gentle ape at all, but a flesh-eating, bone-breaking predator. Broken bones near fossils convinced him these hominins hunted like baboons under stress.

Then he went further. He claimed they used those bones as weapons—clubs, daggers, and tools made from antelope limbs and sharp teeth. He even gave this imaginary toolkit a name: the osteodontokeratic culture. Dart also pointed to evidence of cannibalism, calling human infighting “the mark of Cain.” To him, our ancestors were habitual killers, and civilization only later smothered our carnivorous instincts.

This idea exploded into pop culture when writer Robert Ardrey published African Genesis in 1961. He told the public that humans rose to dominance through violence, weapons, and killing. The book became a bestseller and even inspired Stanley Kubrick. Scientists, however, were horrified. Many still believed humans evolved in Asia and were peaceful herbivores. Ardrey’s killer-ape thesis was social dynamite.

The timing amplified its impact. The world was recovering from two world wars, genocide, nuclear fear, Korea, and Vietnam. Violence felt like humanity’s core trait.

But pushback came. In 1986, UNESCO scientists issued the Seville Statement on Violence, rejecting the idea that war is biological destiny. Violence, they argued, is learned, not inherited.

Still, Dart wasn’t entirely wrong. Humans were more violent in deep time than many thought. But he misread the evidence. Most “bone tools” he described weren’t weapons at all—just the leftovers of carnivores and natural processes.

Chimpanzees

Jill D. Pruetz

Raymond Dart believed aggression set humans apart from apes. But his comparisons with chimpanzees turned out to be wrong. In the 1950s, chimps were thought to be gentle, mostly vegetarian primates. Today, we know they’re tribal omnivores with a long history of hunting and warfare.

Chimp life is political. They live in tight groups with shifting alliances. They split and merge depending on food, movement, and opportunity. And when they hunt, they do it together. Chimps regularly kill and eat colobus monkeys, and some researchers even argue the species are locked in an evolutionary arms race.

But the real shock wasn’t that chimps hunt. It was that they go to war. Male coalitions patrol borders in silence. They look for isolated rivals. They attack only when the numbers guarantee safety. These aren’t chaotic fights. They’re planned ambushes. Scouts move first. The main group follows. The victims are killed, and the attackers seize new territory and mates.

Jane Goodall witnessed this firsthand in the 1970s during the Gombe Chimpanzee War. A single community split into two. Raids began. One group—the Kasakela—systematically killed every adult male in the rival Kahama group. By 1978, the Kahama were wiped out. Their females and territory were absorbed.

Goodall was stunned. She had believed chimps were kinder than humans. Instead, she found they had a dark side—one disturbingly familiar.

Later research revealed the same pattern across Africa. Chimp warfare is widespread. It crosses habitats. It persists over generations.

If chimps patrol borders like us, one question becomes unavoidable: how ancient are these instincts?

Homo Habilis

Jat Matternes

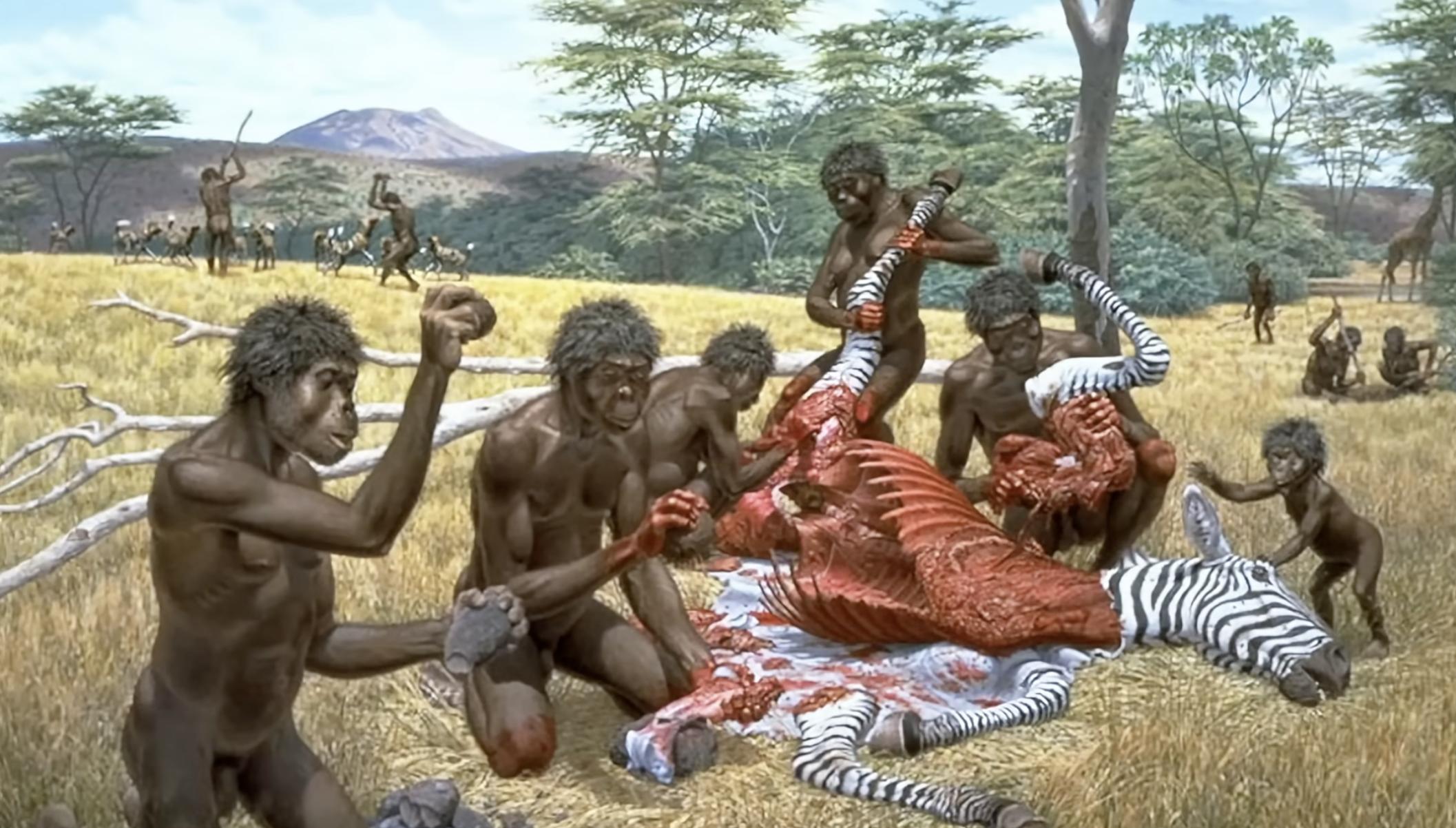

Homo habilis marks a turning point. Living in Africa around 2.5–1.5 million years ago, they had bigger brains, human-like hands, and the first stone tools—the Oldowan industry. Those sharp flakes changed everything. They let early humans slice meat, break bones, and steal resources from carcasses other predators left behind.

Australopithecines ate mostly plants, roots, and insects. But Homo habilis shows clear evidence of regular meat use. At Gona (2.6 Ma), cut-marked bones and Oldowan tools appear together for the first time. Habilis likely scavenged in groups, using stones to intimidate rivals.

By 2 million years ago at Kanjera, early Homo—habilis or emerging erectus—were persistent meat eaters, soon adding fish, turtles, and crocodiles to their diet.

Homo Erectus

Ettore Mazza

Homo erectus took meat eating to the next level. After Homo habilis, they became more proactive and far more strategic. Oldowan flakes were no longer enough. They forged Acheulean handaxes—tools that doubled as lethal weapons. Scavenging shifted into true hunting. Weak apes didn’t suddenly become strong predators. They became organized ones.

How did they catch their prey? Two big ideas dominate.

The first is persistence hunting. Erectus wasn’t fast, but it was built for endurance. Over time they lost body hair, gained sweat glands, shorter toes, springy arches, and S-shaped spines. They stayed cool while their prey overheated. They didn’t win the sprint. They won the marathon. Modern hunter-gatherers still use this method today.

The second hypothesis is ambush hunting. A 2015 study from Olorgesailie in Kenya shows how fault lines and lake basins funneled elephants, hippos, and giant baboons into narrow corridors. Thousands of Acheulean tools and butchered bones were found at these chokepoints. Erectus likely waited in the right place at the right time, using the landscape as a trap. They planned. They cooperated. They predicted animal movement and exploited it.

Their bodies tell the same story. Smaller teeth, weaker jaws, narrower rib cages, and bigger brains all hint at a shift toward calorie-rich food. Anthropologist Richard Wrangham argues that meat and cooking powered these changes. Cooking unlocked more energy. Less chewing shrank our guts and jaws. The saved energy went straight to the brain.

And the jump was massive. From about 600 cc in habilis to nearly 1000 cc in erectus. Something had to fuel that growth.

Taken together—tools, hunting, anatomy—it's hard to avoid the conclusion:

Homo erectus wasn’t just an early human. It was a killer ape.

Homo Sapiens and the Megafauna

Homo erectus eventually branched into many human species—each capable of hunting. Homo sapiens inherited that skill and amplified it. We became even more relentless predators.

During the Pleistocene, Earth teemed with megafauna: mammoths, mastodons, giant kangaroos, elephant birds, saber-toothed cats. But as humans spread, these giants vanished. Archaeology shows why. We had fire. We had advanced tools. We had lethal strategy.

Where humans arrived, megafauna collapsed. North America lost mammoths and giant bison. Australia lost Diprotodon. Madagascar lost elephant birds. Similar patterns hit South America and New Zealand. Some call it a blitzkrieg. Others see a slow decline.

Climate change mattered—but human hunting pushed many species past the point of recovery. These extinctions reveal a hard truth: long before modern weapons, Homo sapiens mastered the art of killing.

Tribes and Tribalism

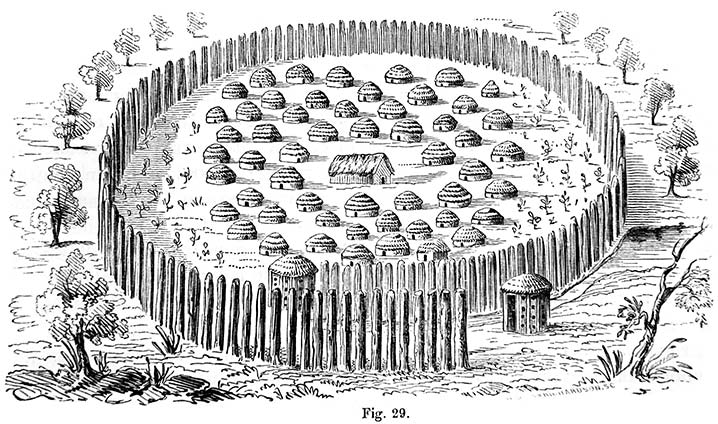

As Homo sapiens spread across the planet, new groups formed, split, and collided. Some encounters were peaceful. Many were not. The deeper we look into hunter-gatherer archaeology, the clearer it becomes: violence is ancient. War didn’t begin with kingdoms or metal weapons. It began long before.

Take Shanidar Cave in Iraq. Ten Neanderthals lived there 35,000–50,000 years ago. Some survived terrible injuries thanks to group care. But others show signs of conflict. Shanidar 3 has a rib wound likely caused by a projectile weapon—something Neanderthals didn’t use. Homo sapiens did. It may be the earliest glimpse of interspecies violence.

Later, between 14,000–18,000 years ago, Jebel Sahaba in Sudan shows a cemetery filled with trauma. Arrow points lodged in bones. Fractured skulls. Repeated attacks. These were hunter-gatherers fighting over shrinking Nile resources.

At Nataruk in Kenya, about 10,000 years ago, we find another massacre. Bodies lay where they fell. Smashed skulls. Bound limbs. Obsidian blades embedded in ribs. No farms, chiefs, or cities—just foragers killing for territory and survival.

The pattern continues into recent prehistory. The Americas show abundant evidence of warfare long before Europeans arrived: fortified villages, burned settlements, mass graves, and projectile injuries. Places like Castle Rock, Crow Creek, and Casas Grandes reveal raids, scalping, and organized combat between A.D. 1000–1400.

Modern hunter-gatherers show the same tendencies. Raids, ambushes, revenge attacks, and territorial fights are common between groups, even when internal life is peaceful. Like chimps, most conflicts are surprise strikes delivered with overwhelming advantage.

The conclusion is stark: ancient humans didn’t need cities or kings to make war. Hunter-gatherers fought because the stakes—land, mates, food—were life and death.

Sources:

[1] Darwin, C. 1871. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. John Murray.

[2] Bramble, D. and Lieberman, D. 2004. “Endurance running and the evolution of Homo.” Nature 432:345–352.

[3] Wrangham, Richard W. 2009. Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human. New York, NY: Basic Books

[4] Dart, R. 1953. “The Predator Transition From Ape To Man.” International Anthropological and Linguistic Review 1(4).

[5] Ardrey, R. 1961. “African Genesis: A Personal Investigation Into the Animal Origins and Nature of Man.” New York: Atheneum.

[6] Pickering, T. 2012. African Genesis revisited: reflections on Raymond Dart and the ‘predatory transition from ape(-man) to man.’ In: Reynolds SC, Gallagher A, eds. African Genesis: Perspectives on Hominin Evolution. Cambridge Studies in Biological and Evolutionary Anthropology. Cambridge University Press; 487-505.

[7] Boesch, C. 1994. “Chimpanzees-red colobus monkeys: a predator-prey system.” Animal Behaviour 47(5):1135-1148.

[8] Wrangham, R. and Glowacki, L. 2012. “Intergroup aggression in chimpanzees and war in nomadic hunter-gatherers: evaluating the chimpanzee model.” Hum Nat. 23(1):5-29.

[9] Goodall, J., et al. 1979. “Intercommunity interactions in the chimpanzee population of the Gombe National Park.” In: The Great Apes (Ed. by Hamburg, D. A. & McCown, E. R.), pp. 13-53. Menlo Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings.

[10] Boesch, C, et al. 2008. “Intergroup conflicts among chimpanzees in Taï National Park: lethal violence and the female perspective.” Am J Primatol. 70(6):519-32.

[11] Drummond-Clarke, R., et al. 2023. “A case of intercommunity lethal aggression by chimpanzees in an open and dry landscape, Issa Valley, western Tanzania.” Primates. 64(6):599-608.

[12] A Brief History of the Gombe Chimpanzee War

[13] Evidence for Meat-Eating by Early Humans

[14] Semaw, S., et al. 1997. “2.5-million-year-old stone tools from Gona, Ethiopia.” Nature 385, 333–336.

[15] Pobiner, B. 2015. “New actualistic data on the ecology and energetics of scavenging opportunities.” Journal of Human Evolution 80: 1–16.

[16] Ibid. Bramble, D. and Lieberman, D.

[17] Kübler, S., et al. 2015. “Animal movements in the Kenya Rift and evidence for the earliest ambush hunting by hominins.” Sci Rep 5, 14011.

[18] Ibid. Wrangham

[19] Churchill, S., et al. 2009. “Shanidar 3 Neandertal rib puncture wound and paleolithic weaponry.” Journal of Human Evolution 57(2):163-178.

[20] Lombard, M. and Phillipson, L. 2010. “Indications of bow and stone-tipped arrow use 64,000 years ago in KwaZulu-Natal.” South Africa 84(325):635-648.

[21] Crevecoeur, I., et al. 2021. “New insights on interpersonal violence in the Late Pleistocene based on the Nile valley cemetery of Jebel Sahaba.” Sci Rep 11, 9991.

[22] Lahr, M., et al. 2016. “Inter-group violence among early Holocene hunter-gatherers of West Turkana, Kenya.” Nature 529, 394–398.

[23] Lambert, P. 2002. “The Archaeology of War: A North American Perspective.” Journal of Archaeological Research 10(3).