By: Greg Schmalzel

Decades ago, researchers found a crushed skull in Hubei, central China. This year it was digitally restored. The new analysis challenges parts of our story about human origins — but only if its model holds up. It’s a million years old and researchers say it belongs to an Asian human lineage that us Homo sapiens evolved alongside. If this is right, what does that do to the neat story that ‘humans evolved in Africa’? Today, we’ll unpack this fossil and explore its implications for our own evolution.

Is Asia the new frontier of human evolution? Let’s see where the evidence leads.

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Out of Africa

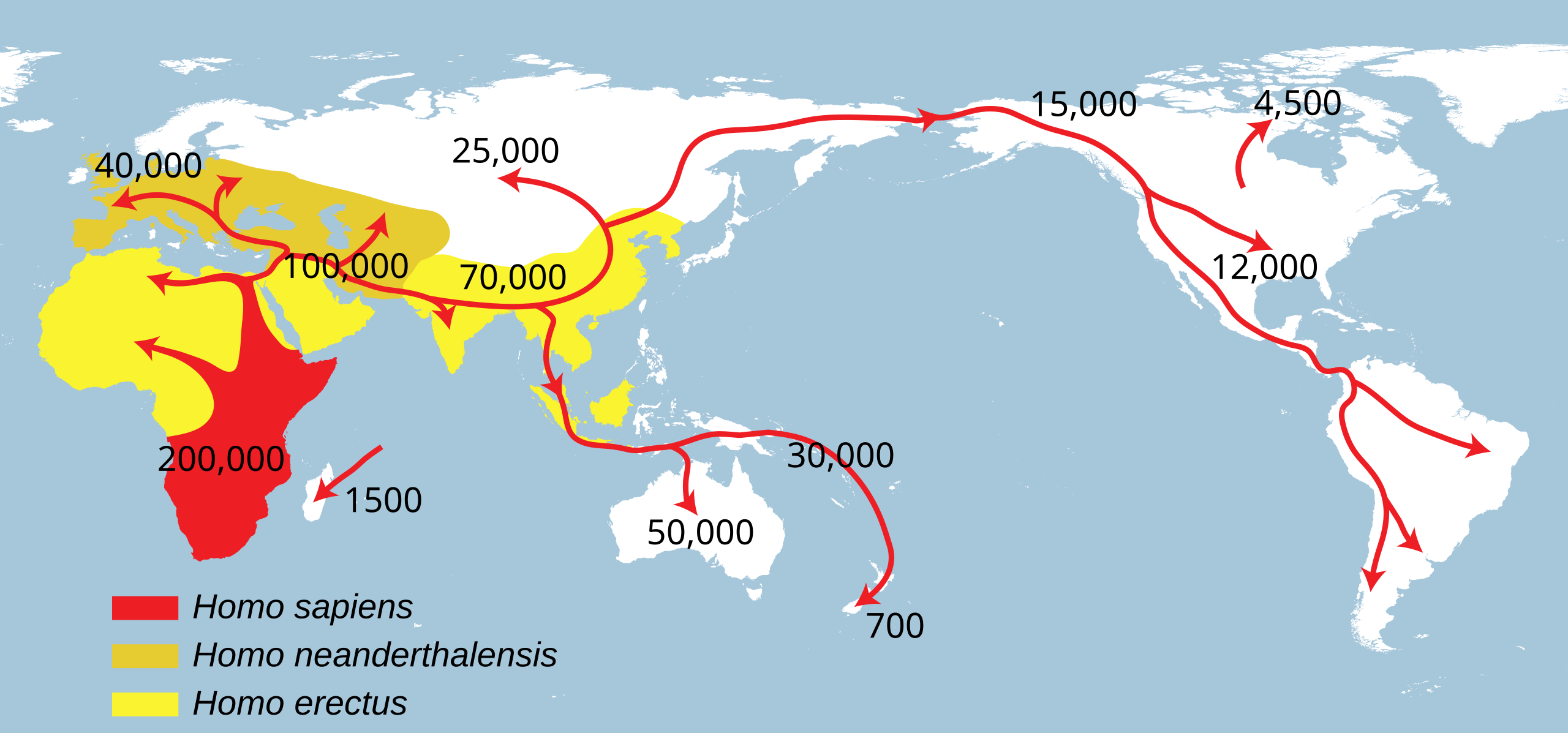

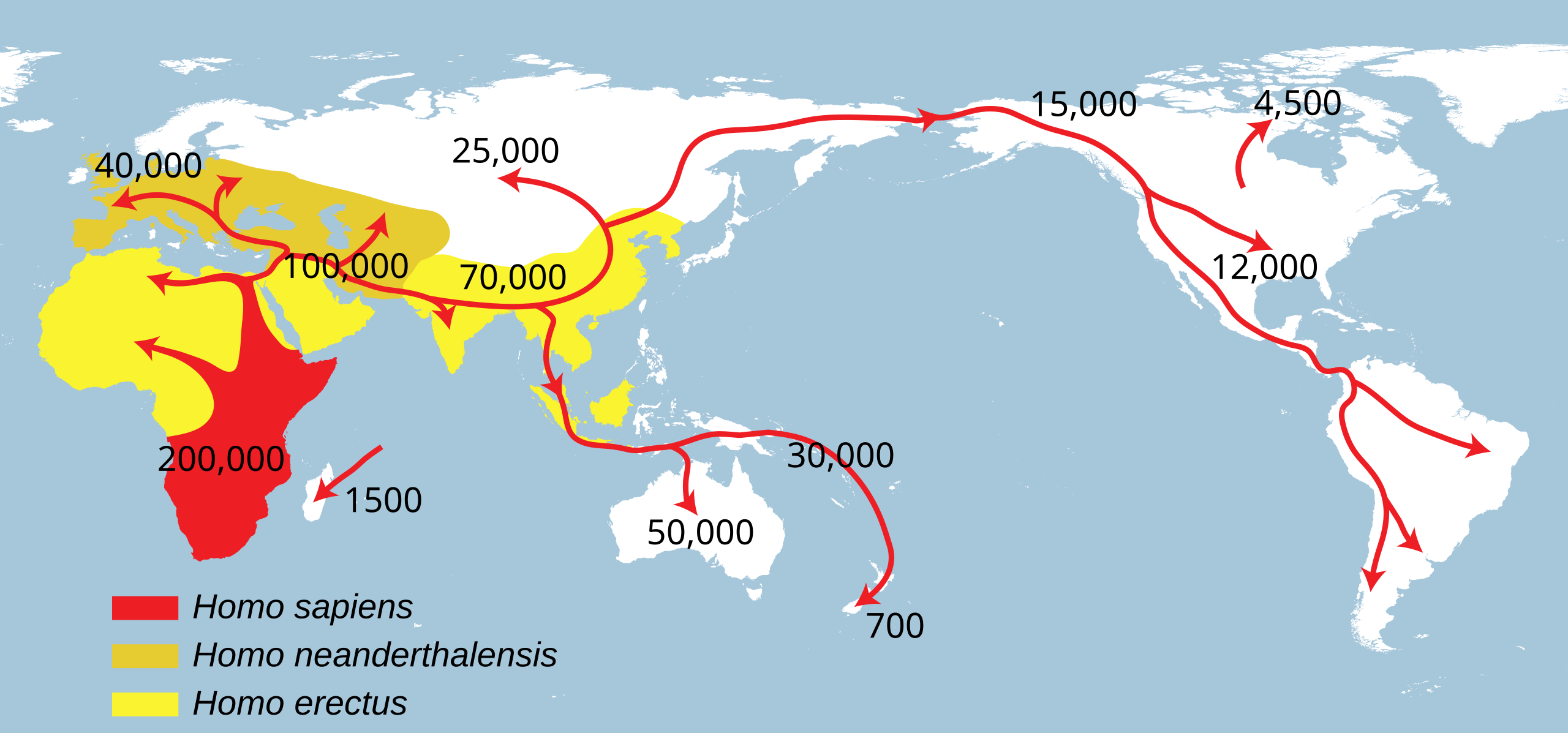

For decades, the story of human origins has pointed to Africa. Fossils, tools, and DNA all seemed to show that Homo sapiens evolved there before spreading across the globe. Climate shifts in Africa pushed our ape ancestors out of forests and onto open ground, driving bipedalism, tool use, and eventually bigger brains. Over millions of years, species like Australopithecus, Homo habilis, and Homo erectus appeared in Africa before any counterparts elsewhere.

By about 300,000 years ago, modern humans emerged — their genetic diversity still greatest in Africa today. Small groups later migrated outward around 50–70,000 years ago, mixing with species like Neanderthals. For that reason, Africa has long been seen as the cradle of humankind. But now, a newly analyzed fossil from China dating to roughly one million years ago is challenging that narrative — forcing scientists to ask whether our evolutionary roots might be more complex than we thought.

The Yunxian Discovery

Gary Todd

Gary Todd

The fossil in question is Yunxian 2, one of three ancient human skulls found in Hubei, central China. Discovered in 1989 and 1990, the first two skulls were badly crushed under heavy sediment, and we hardly know anything about Yunxian 3 yet. For years, scientists tentatively called them Homo erectus, but the facial structure looked unusually modern — somewhat more like Homo sapiens. Recent dating using electron spin resonance and U-series analysis on the surrounding soil and teeth revealed the fossils are about 1 million years old.

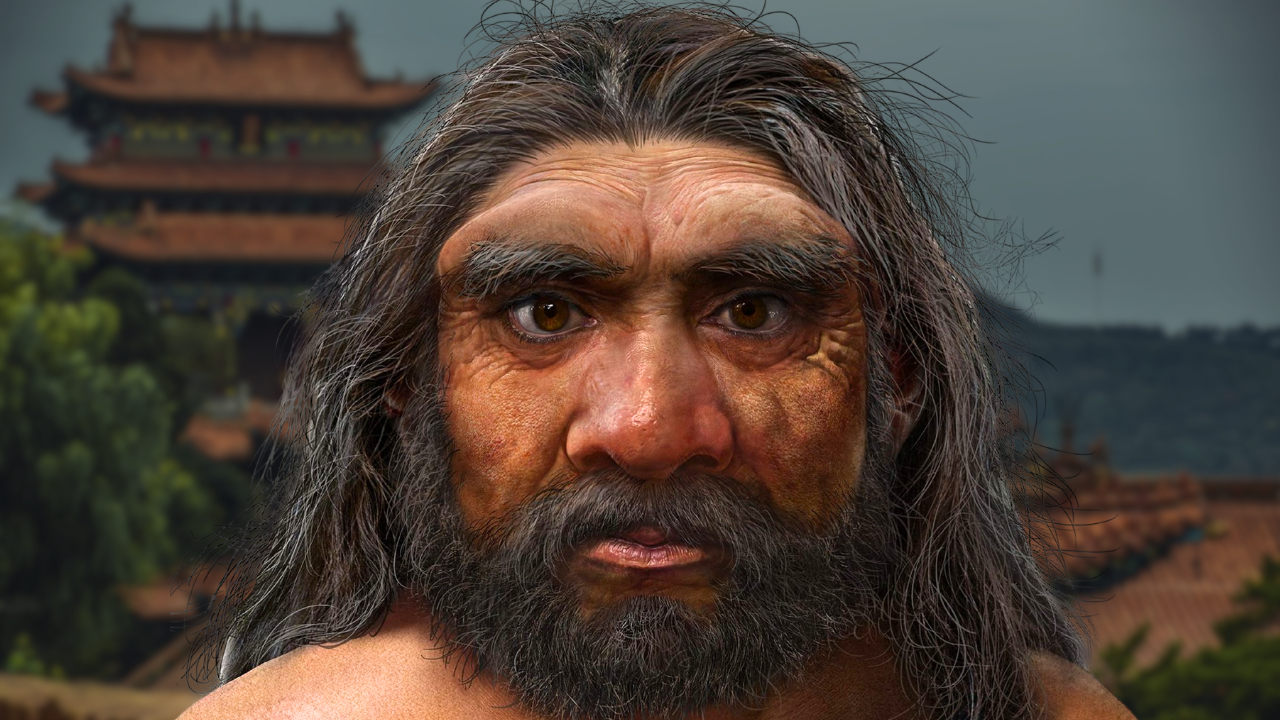

Then, in 2025, researchers digitally restored Yunxian 2 using CT scanning and 3D retrodeformation. Their reconstruction suggested it wasn’t Homo erectus at all, but Homo longi — a species recently linked to the mysterious Denisovans. If true, it would mean this ancient lineage evolved in East Asia long before modern humans emerged in Africa, hinting that our evolutionary story may be more complicated — and more global — than once thought.

Homo longi

Jiannan Bai and Xijun Ni2

Jiannan Bai and Xijun Ni2

Denisovans and The Dragon Man Skull (Harbin)

Xijun Ni

Xijun Ni

The Harbin cranium, or “Dragon Man,” is one of the most complete and impressive human fossils ever found in East Asia. Discovered in northeast China in the 1930s, it’s massive and shares many traits with Yunxian 2. In 2021, scientists named it Homo longi, suggesting it represents a distinct human lineage in Asia. At about 150,000 years old, it’s far better preserved than Yunxian, even keeping a tooth intact. From calcified plaque on that tooth, researchers extracted DNA that matched Denisovans. Protein tests confirmed it. This means Homo longi—and likely Yunxian 2—belonged to the mysterious Denisovan branch of humanity.

Before recent breakthroughs, Denisovans were known from only a few sites—most famously Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains. In this icy, remote landscape, archaeologists uncovered tiny remains: a finger bone and a few teeth, dating between 300,000 and 50,000 years ago. They lived alongside both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens. The cave also held a treasure trove of artifacts—stone tools, bone needles, beads, and ornaments—evidence of culture and craftsmanship.

Their range expanded dramatically in 2019, when a 160,000-year-old jawbone from Tibet’s Baishiya Karst Cave was identified as Denisovan through protein analysis. This showed they could survive high altitudes with little oxygen. Farther south, a 150,000-year-old molar from Laos and a jawbone dredged from the Penghu Channel off Taiwan also matched Denisovan proteins.

Together, these finds stretch Denisovan territory from Siberia’s frozen caves to Southeast Asia’s humid coasts—proof they were adaptable, wide-ranging humans. If Homo longi and Denisovans are indeed the same, their story spans nearly all of eastern Asia, suggesting a deep, complex chapter of human evolution still unfolding.

Genetics And How This Challenges Out Of Africa

If it truly represents the skull of a Denisovan, then it pushes the emergence of this amazing species to over 1 million years ago. This would indicate that our species is much older too. Why is that? Because us, Neanderthals, and Denisovans are all related. We share a common ancestor who lived a very long time ago. And the authors of this study have just shaken up who that ancestor was. So in addition to reconstructing the skull, they’ve also reconstructed the evolutionary timeline. This is where things get interesting. We need to first look at the conventional timeline. This is going to require some genetics.

Jiannan Bai and Xijun Ni2

Xijun Ni

Gary Todd

Gary Todd