LiDAR Exposes Lost Cities in the Amazon

Sep 29, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

Archaeologists were wrong about the Amazon. For years, this rainforest was painted as an untouched wilderness, incapable of supporting complex societies. But new tools are revealing networks of plazas, roads, and fertile farms hidden beneath the canopy. These discoveries are actively rewriting the story of the Amazon. The old story was about an inhabitable jungle. The new story is about human-shaped landscapes, engineered soils, and garden cities. And we’re lucky enough that this is all happening within our lifetime.

I want to bring awareness to these lost cities and show how archaeological paradigms can always shift. So let’s dive into what’s really hidden within the Amazon, and the myths that are now toppling over.

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

Myth of the Pristine Amazon

For much of the 20th century the Amazon was called a “counterfeit paradise.” Betty Meggers coined the phrase to argue that the rainforest’s thin, acidic soils couldn’t support large, permanent societies. In her view, any complex settlement would have collapsed—so the lack of obvious ruins meant the region was simply unsuitable for long-term farming.

Other archaeologists agreed. They pointed to scattered artifacts, poor preservation, and little visible architecture as proof that people lived in small, mobile bands. Slash-and-burn gardening was presented as the only realistic subsistence strategy: short-term, low-yield, and incompatible with cities. Dense vegetation, shifting rivers, and perishable wooden tools were also offered as reasons why ancient Amazonia seemed empty.

The net effect was a dominant story: the Amazon as a fragile, lightly used wilderness where humans left barely perceptible traces. That assumption shaped research priorities for decades. Scholars largely stopped looking for big settlements and focused on models of low population density and ephemeral occupation. In short, the “pristine Amazon” idea became the default lens through which generations of archaeologists read the rainforest—until new evidence began to challenge it.

Colonial Explorers

For decades scholars shrugged off early explorer accounts as exaggeration. Meggers and others argued that any reports of big Amazonian towns must be misreadings or short-lived flukes. The forest, they said, couldn’t sustain cities.

But the 1500s witnesses tell a different story. Francisco de Orellana sailed down a river lined with clustered houses on raised platforms. He saw plazas, docks full of canoes, and markets bustling with trade. Gaspar de Carvajal—who kept detailed notes—described rows of permanent houses, fields beside villages, bridges and long paths linking settlements across swamp and forest. Where Europeans expected camps, they found organized towns.

Whether every detail is literal or filtered through sixteenth-century eyes, the pattern repeats: coordinated settlement, farming, and infrastructure. Those early reports were not pure fantasy. Now, with LiDAR, soil science, and archaeology, many of their observations are being confirmed. The question isn’t whether they exaggerated—it’s how much of what they saw we’re only now beginning to read.

What is LiDAR?

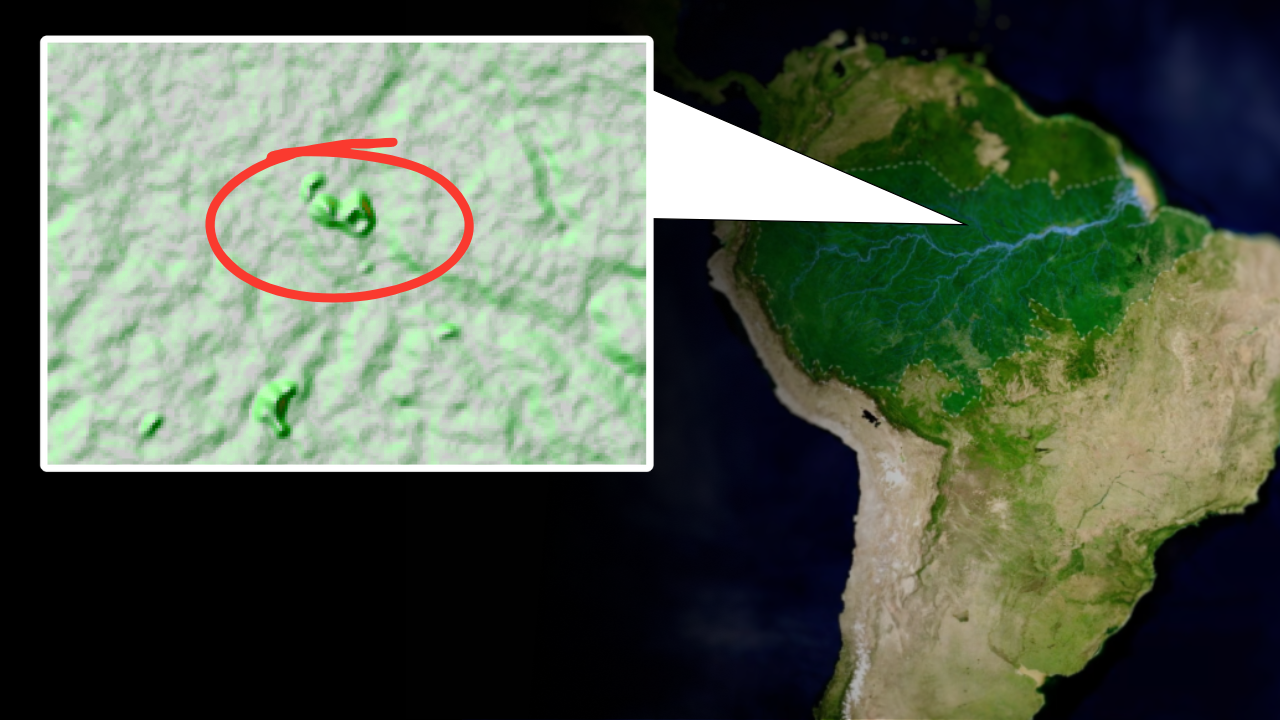

One of Meggers’ main points was that thick forest hides ancient remains — a problem in mid-20th century archaeology. Today LiDAR solves that. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) is like an X-ray for landscapes: aircraft fire millions of laser pulses, measure returns, and build dense 3D "point clouds" that reveal terrain, roads and subtle earthworks. Because some pulses slip through canopy gaps, LiDAR maps ground under trees. It’s fast, precise, cheaper and safer than blind ground searches. Think of LiDAR as a screening tool — it shows where to dig and avoids wasted effort. Next: recent discoveries.

The Lost Cities

H. Prümers/German Archaeological Institute

LiDAR is rewriting Amazon history — fast. In Bolivia, airborne scans of the Casarabe culture revealed huge, engineered towns. Two centers, Cotoca (≈150 ha) and Landívar (≈315 ha), sit inside moats and ramparts. Tall conical pyramids, U-shaped platforms, straight causeways and a 7-km canal show massive coordinated labor. Researchers call it low-density urbanism — diffuse cities tied to intensive landscape engineering.

In Ecuador, Stéphen Rostain’s LiDAR plus two decades of fieldwork mapped 300 km² of the Upano Valley. The data revealed 6,000+ earthen platforms, fifteen town clusters (Sangay, Kilamope, Copueno), planned plazas, terraces, canals and four road types — including straight-dug paths 2–3 m deep and routes stretching 14–25 km. Excavations match the map: postholes, storage jars, grinding stones, charred seeds and starch residues for maize, manioc, beans, sweet potato — even traces of chicha brewing. Dates span ~500 BCE to 1200 CE. Rostain calls this “garden urbanism” — settlements woven into purposely managed ecosystems.

A wider LiDAR sweep (5,315 km²) uncovered 24 new earthworks across the basin. Statistical models extrapolate thousands more. One estimate suggests up to ~23,000 undocumented earthworks, meaning most engineered places remain hidden. Hotspots cluster in southwestern Amazonia where clayey soils, plateau settings and proximity to water favored earth-building.

Taken together, these studies flip the old myth of an empty Amazon. The forest hides cities, farms and canals. It was shaped, in many places, by people practicing large-scale agriculture, engineering water, and building dispersed urban networks. The more we look, the more the jungle reveals its human past.

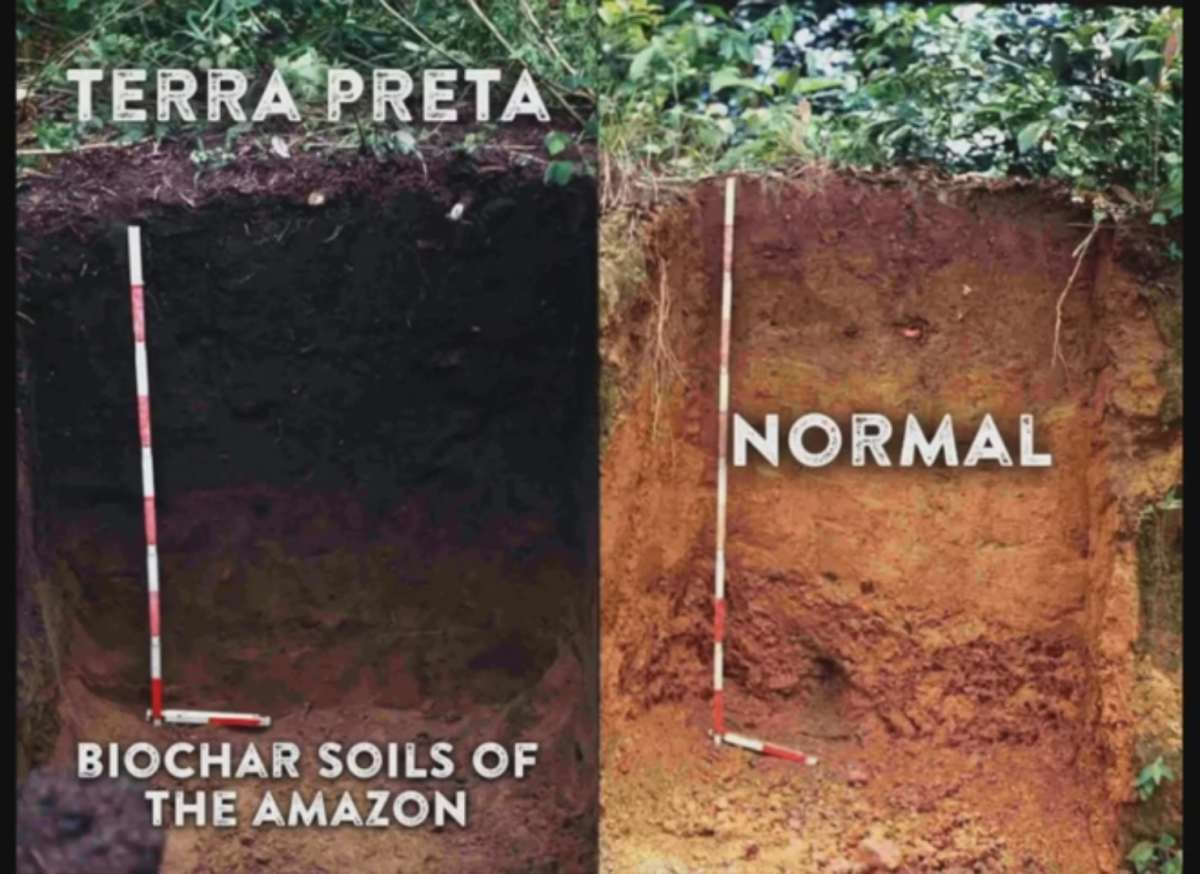

Terra Preta

For decades scholars argued Amazon soils were too poor for big farms. Terra preta changed that story. Terra preta is human-made “black earth.” Over centuries, people mixed charcoal, pottery shards, food waste and ash into the ground. The result: deep, carbon-rich soil that holds nutrients and stays fertile.

Hatahara offers a clear example. This 16-hectare site preserves stacked occupations, ten earthen mounds, hearths, pits, bones and even human burials. The mounds were built with ADE (terra preta) itself — a sign that fertile soil was abundant, not scarce. Excavations show sustained farming, storage and ritual life across centuries.

On a landscape scale, terra preta is patchy but important. Models place it across about 3.2% of Amazonia (~154,000 km²), concentrated along rivers, bluffs and central–eastern forests. Where it appears, it marks long-term settlements and intense food production. Some estimates suggest pre-Columbian populations in these zones may have reached millions.

Plant domestication grew with these systems. Indigenous peoples domesticated at least 83 native species—manioc, maize, sweet potato, cacao, peppers and many trees. Domestication was gradual: tending wild plants in gardens, then selecting and propagating the best. By ~4,000 BP many communities shifted to settled farming, creating orchards and anthropogenic forests.

In short: terra preta is proof. Where it exists, the Amazon was a lived, engineered landscape — not an untouched wilderness.

The Future of Amazonian Archaeology

The “pristine Amazon” idea is dead. LiDAR and terra preta reveal a patchwork of lost towns, canals, and engineered soils. People shaped the forest — not the other way around.

Now AI is turbocharging discovery. Machine learning scans LiDAR and satellite data for straight edges, mounds, causeways and canopy disruption. What took teams weeks can take models hours. Deep networks pick out faint earthworks, fuse ecological clues and build 3D site reconstructions for virtual fly-throughs. Models learn from verified sites and tighten their predictions.

A recent global contest — the OpenAI-to-Z Challenge — pushed this frontier. Competing teams trained models on LiDAR, elevation layers and large language models. The winners, Black Bean, flagged 67 square-mile patches as high-priority leads. The contest drew thousands of participants and produced dozens of new targets for follow-up survey.

These leads aren’t proofs. They’re pointers. Fieldwork still verifies context, dates and meaning. And speed brings real risks: looting, biased sampling, and overclaiming without excavation. Responsible AI needs transparent methods, Indigenous partnership, and careful publication. Done right, machine learning won’t replace archaeologists — it will amplify them, turning noisy data into precise places to dig, listen, and learn. The jungle is finally giving up its secrets.

Sources:

[1] Meggers, B. 1971. Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise.

[2] Panko, B. 2017. “The Supposedly Pristine, Untouched Amazon Rainforest Was Actually Shaped By Humans” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/pristine-untouched-amazonian-rainforest-was-actually-shaped-humans-180962378/

[3] Prümers, H., et al. 2022. “Lidar reveals pre-Hispanic low-density urbanism in the Bolivian Amazon.” Nature” 606, 325–328.

[4] Lombardo, U. 2010. “Pre-Columbian human occupation patterns in the eastern plains of the Llanos de Moxos, Bolivian Amazonia.” Journal of Archaeological Science.

[5] Rostain, S., et al. 2024. “Two thousand years of garden urbanism in the Upper Amazon.” Science 383, 6679.

[6] Peripato, V,. et al. 2023. “More than 10,000 pre-Columbian earthworks are still hidden throughout Amazonia.” Science 382(6666):103-109.

[7] Lombardo, U., et al. 2022. “Evidence confirms an anthropic origin of Amazonian Dark Earths.” Nat Commun 13, 3444.

[8] Balée, W. and Clark, E. 2006. “Time and complexity in historical ecology: Studies in the Neotropical Lowlands.” Columbia University Press.

[9] McMichael C. H., et al. 2014. “Predicting pre-Columbian anthropogenic soils in Amazonia.” Proc. R. Soc. B. 28120132475.

[10] Clement Charles R., et al. 2015. “The domestication of Amazonia before European conquest.” Proc. R. Soc. B.28220150813.

[11] Levis, C., et al., 2017. “Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition.” Science 355,925-931.