Did Cavemen Actually Exist?

Oct 13, 2025

By: Greg Schmalzel

When I say the word “Caveman”, what image pops into your head? Do you envision a hairy ape-like man with a club? Maybe you thought of one of the Flintstones characters from the 1960s cartoon. Most people probably imagine one or the other, and I feel as though they never really question if humans like this really existed. If you’re one of them, I hate to break it to you, but these are some seriously flawed conceptions about cavemen.

The truth is that they did exist, but in ways that are far more nuanced and impressive than we often consider. The evidence shows how the truth is far stranger and more human than any cartoon.

For the full YouTube video, click HERE.

The Origin of “Cavemen”

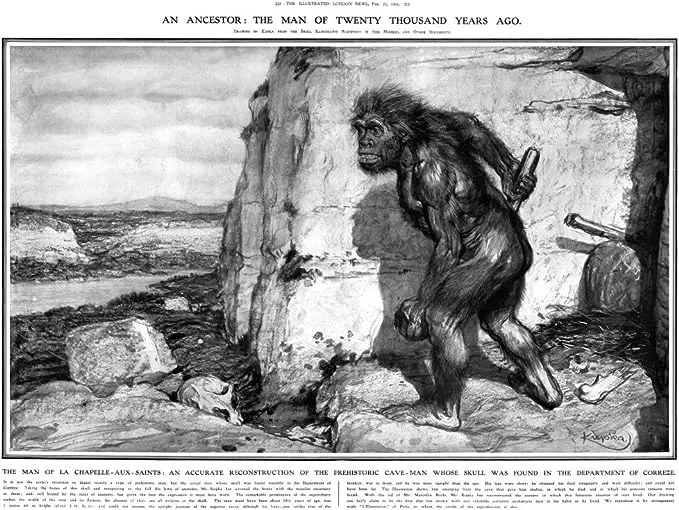

Marcellin Boule’s reconstruction of the “Old Man”.

Where did “caveman” come from? The word shows up in English in the 1860s. Back then it simply meant people whose bones or tools were dug from caves. Amateur digs across Europe found human remains with extinct animals. That signaled great age.

Early finds mattered. In 1829 a child skull from Engis (Belgium) sat with extinct hyenas and rhinos. In 1856 quarry workers in the Neander Valley dug up the Feldhofer specimen — the first widely recognized Neanderthal. More big finds followed, like Spy (Belgium) in 1886 and La Chapelle-aux-Saints in France. Marcellin Boule’s reconstruction of the “Old Man” looked stooped and brutish. Museums and books echoed that image for decades.

Popular culture finished the job. Writers and filmmakers borrowed the image. Silent films, comics, and cartoons turned the idea into a visual shorthand. The caveman became a hairy, club-wielding stereotype. Movies even paired humans and dinosaurs — a flat-out error that stuck as a joke in comics and TV. The Flintstones perfected the gag.

That stereotype hides reality. “Caveman” collapses many species and millennia into one cartoon. Different hominins used caves at different times. Caves were rarely the only or constant homes. People camped, sheltered, worked, buried their dead, and used open-air sites too.

Part of the problem is preservation bias. Caves protect evidence. They block wind, rain, and sunlight. Stable conditions slow decay of bone, charcoal, and organic tools. Sediments bury hearths and artifacts. Open-air sites often wash away or rot. That makes caves over-represented in the record.

Caves come in many types — limestone chambers, lava tubes, rock shelters, and sea caves — each with its own story. Because caves preserve so well, they tell vivid tales. But they don’t tell the whole tale. Next, we’ll look at what the archaeology actually says about who lived in caves and why.

The Archaeological Reality

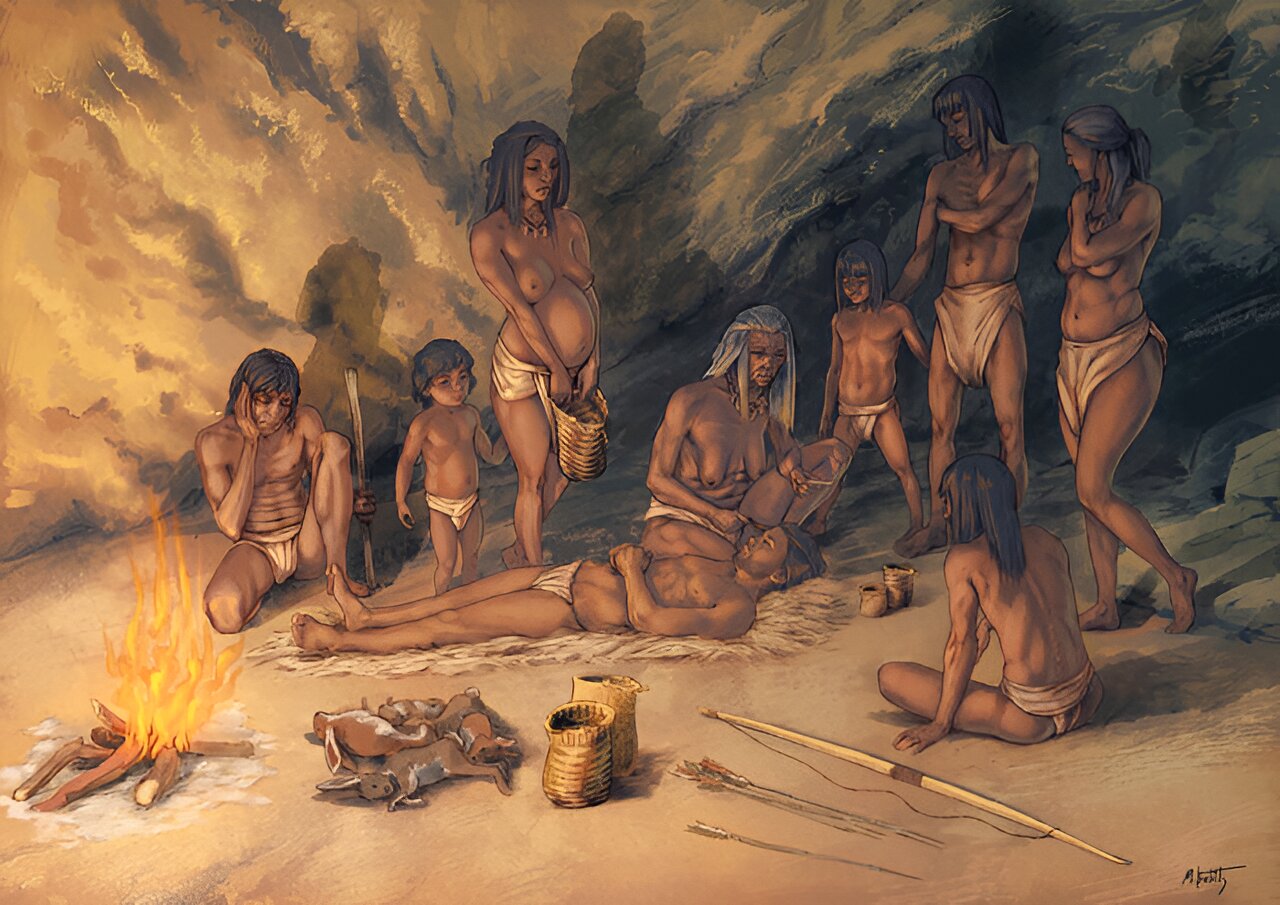

Moisés Belilty Molinos

Homo erectus turned caves into footholds. Emerging ~2 million years ago, they walked out of the trees and into the open. Caves offered shelter, protection, storage, and energy savings. Wonderwerk (South Africa) hints at early fire use ~1 million years ago. Zhoukoudian (near Beijing) shows repeated occupation and huge tool assemblages. These sites mark long migrations and bold exploration.

Neanderthals came later. They ranged across Europe and western Asia from ~400–40 kya. They hunted, tended the injured, and used fire and tools. Bruniquel (France) revealed massive stalagmite constructions 175–177 kya. Neanderthals broke and stacked 400 pieces deep in the cave. Fires blacken the stones.

Planning and teamwork are obvious. Shanidar (Iraq) shows deliberate burials and possible ritual care. Neanderthals were complex people, not cartoon brutes.

Denisovans are mostly a genetic story. Discovered in Denisova Cave (Siberia), they lived from ~300–30 kya. DNA links them with Neanderthals and modern humans. They left lavish ornaments — bracelets, beads, and pendants — showing craft and style.

Rising Star (South Africa) dumped a bombshell: Homo naledi. Over 1,500 bones from ~15 individuals came from a deep chamber. Small bodies, mixed anatomy, and debated burial claims spark fierce debate. H. naledi forces fresh thinking about rituals and disposal.

Flores brought tiny people: Homo floresiensis. Liang Bua cave yielded small-bodied skeletons and sophisticated tools. Island life reshaped bodies but not ingenuity.

Modern humans left vivid marks. Blombos (South Africa) records beads, ochre, and symbolic behavior 75–100 kya. Jerimalai (Timor) shows deep-water fishing and shell hooks ~42 kya. Lascaux (France) gives us stunning cave art 17–22 kya. And Mesa Verde proves caves and cliff dwellings were recent homes, adapted and engineered by Pueblo peoples.

Different species. Different lives. Caves preserve striking snapshots. But they do not make one single “caveman.” The truth is richer, stranger, and far more human.

Did Neanderthals Hibernate?

Neanderthals may not fit the cartoon “caveman,” but a bold new idea has surfaced: seasonal hibernation. Hibernation is a deep slowdown of metabolism, body temperature, heart rate, and breathing. Animals use it to survive cold and food shortage. It’s rare in primates because big brains need steady fuel. One primate exception is the fat-tailed dwarf lemur. So the question is fair: could some ancient hominins do something similar under extreme pressure?

Climate swung wildly in the Pleistocene. Glacials cooled Europe 5–10 °C on average. Summers could be mild; winters brutal. At Gorham’s Cave, data show winters were harsher even when annual temps were only slightly lower. Neanderthal summers likely looked like ours—mixed hunting and gathering. Winters may have been different.

Bones from Sima de los Huesos show odd lesions. Tunnels in spongy bone. Patches of new growth. A “rotten fence-post” texture. Young individuals show many of these signs. The pattern resembles damage in hibernating animals. Some researchers suggest cycles of torpor with brief arousals. Cave bears from the same system show similar changes.

The idea is intriguing. But problems remain. Lesions can come from disease, malnutrition, or other stresses. Neanderthal samples are small and patchy. And large brains demand steady energy—true hibernation slashes metabolism in ways brains may not tolerate.

For now, hibernating Neanderthals are a provocative hypothesis. It opens a new window on cave life. But it is far from proven.

Sedimentary Ancient DNA (SedaDNA)

Richard ‘Bert’ Roberts

The more we dig, the fewer caveman myths hold up. A new tool is changing the game: sedimentary ancient DNA, or sedaDNA. It reads DNA trapped in dirt, not bones. Tiny fragments of people, animals, plants, and microbes hide in cave sediments. Caves preserve them well. Stable temps and low light slow decay. SedaDNA tells us who used a site, when, and what they ate — even without bones.

Denisova Cave shows the power of this approach. Soil DNA reveals long stretches of Denisovan presence. But between about 90–120 kya, only Neanderthal DNA appears. That gap would be invisible from the tiny number of fossils alone. Faunal DNA tracks climate change too. Cave bears give way to brown bears as environments shift. Hyena types change. The whole ecosystem moves with the weather.

There’s more. Scientists can now extract DNA from artifacts without destroying them. A deer-tooth pendant from Denisova yielded human and deer genomes. Dating puts it at ~19–25 kya. The human DNA comes from a woman linked to Ancient North Eurasian groups. That turns a bead into a biography.

SedaDNA and artifact DNA shrink the past from populations to people. We stop saying “cavemen” and start meeting cavewomen, children, makers, and wearers. Archaeology is finally getting intimate.

Sources:

[1] Horwitz, L. and Chazan, M. 2015. “Past and Present at Wonderwerk Cave (Northern Cape Province, South Africa).” Afr Archaeol Rev 32, 595–612.

[2] Berna, F., et al. 2012. “Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa.” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 May 15;109(20):E1215-20.

[3] Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian

[4] SHANIDAR Z: What did Neanderthals do with their dead?

[5] Solecki, R. 1975. “Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Flower Burial in Northern Iraq.” Science 190, 880-881.

[6] Krause, J., et al. 2010. “The complete mitochondrial DNA genome of an unknown hominin from southern Siberia.” Nature 464(7290):894-7.

[7] Qin, P. and Stoneking, M. 2015. “Denisovan Ancestry in East Eurasian and Native American Populations.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 32(10):2665–2674.

[8] Derevianko, O., et al 2020. “Who Were the Denisovans?” Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 48(3):3-32.

[9] Derevianko, A., et al. 2008. “A Paleolithic Bracelet from Denisova Cave.” Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 34(2):13-25.

[10] Dirks, P., et al. 2015. “Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa.” Elife. 2015 Sep 10;4:e09561.

[11] Berger, L., et al. 2023. “Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi.” eLife 12:RP89106.

[12] Vanhaeren, M., et al. 2013. “Thinking strings: additional evidence for personal ornament use in the Middle Stone Age at Blombos Cave, South Africa.” Journal of Human Evolution 64(6):500-17.

[13] Henshilwood, C., et al. 2011. “A 100,000-Year-Old Ochre-Processing Workshop at Blombos Cave, South Africa.” Science 334, 219-222.

[14] Prehistoric Sites and Decorated Caves of the Vézère Valley

[15] Mesa Verde National Park - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

[16] Pederzani, S., et al. 2021. “Reconstructing Late Pleistocene paleoclimate at the scale of human behavior: an example from the Neandertal occupation of La Ferrassie (France).” Sci Rep 11, 1419 (2021).

[17] Blain, H.,et al. 2013. “Climatic conditions for the last Neanderthals: Herpetofaunal record of Gorham’s Cave, Gibraltar.” J Hum Evol. 64(4):289-99.

[18] Bartsiokas, A. and Arsuaga, J. 2020. “Hibernation in hominins from Atapuerca, Spain half a million years ago” L'Anthropologie 124(5):102797.

[19] Early humans may have survived the harsh winters by hibernating

[20] Jaubert, J., et al. 2016. “Early Neanderthal constructions deep in Bruniquel Cave in southwestern France.” Nature 534, 111–114.

[21] Langley, M., et al. 2016. “42,000-year-old worked and pigment-stained Nautilus shell from Jerimalai (Timor-Leste): Evidence for an early coastal adaptation in ISEA.” J Hum Evol. 97:1-16.

[22] O’Connor, S., et al. 2011. “Pelagic Fishing at 42,000 Years Before the Present and the Maritime Skills of Modern Humans.” Science 334,1117-1121.

[23] Brown, A., et al. 2024. “The sedaDNA revolution and archaeology: Progress, challenges, and a research agenda.” Journal of Archaeological Science 174.

[24] Zavala, E., et al. 2021. “Pleistocene sediment DNA reveals hominin and faunal turnovers at Denisova Cave.” Nature 595, 399–403.

[25] Slon, V., et al., 2017. “Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from Pleistocene sediments.” Science 356, 605-608.

[26] Brown, P., et al. 2004. “A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia.” Nature 431, 1055–1061.

[27] Kaifu, Y., et al. 2024. “Early evolution of small body size in Homo floresiensis.” Nat Commun 15, 6381.

[28] Essel, E., et al. 2023. “Ancient human DNA recovered from a Palaeolithic pendant.” Nature 618, 328–332.